Holy Crap!!! I was all set to do a post on Fidelity’s zero-fee mutual funds as a follow up to last Wednesday’s post on index mutual funds. But the stock market has had other ideas. So far this month stocks have tumbled 12%. 12!!!

There seems like a lot going on that we need to process, so let’s start breaking this down.

Dec 2018 in context

There’s still a week to go, but as it stands right now, stocks are down 12% for the month. Of course there’s one more week left in the month so things could go up and it won’t be as bad, or things could get worse and . . . well, let’s try to stay positive.

No matter how you slice it, 12% is a lot. Just to put it in perspective, since 1950, when the S&P 500 started, there have been 828 months, and Dec 2018 ranks as the 4th worst month of all time. In 70ish years we’re in the midst of the 4th worst month.

Think of this as a generational storm. I don’t know if that’s comforting or dispiriting. Months like this happen, and it has been worse in the past, yet this is on the Mount Rushmore of all-time bad investing months.

Just in case you’re wondering what the 10 worst months for the S&P 500 are, here you go:

| Month ending | S&P 500 close | Return |

| Oct-87 | 252 | -21.8% |

| Oct-08 | 969 | -16.9% |

| Aug-98 | 957 | -14.6% |

| Dec-18 | 2417 | -12.4% |

| Sep-74 | 64 | -11.9% |

| Nov-73 | 96 | -11.4% |

| Sep-02 | 815 | -11.0% |

| Feb-09 | 735 | -11.0% |

| Mar-80 | 102 | -10.2% |

| Aug-90 | 323 | -9.4% |

Sit tight

What’s done is done. The stock market has cratered, and unless you have a time machine, you just need to accept this really tough month and then look to the future. That’s where I think things get a lot more comforting.

You can take that table above and then add two additional pieces of data: how stocks did in the next month and how stocks did over the next year. That paints a completely different picture.

| Month | S&P 500 close | Return | Next month return | Next 12-month return |

| Oct-87 | 252 | -21.8% | -8.5% | 21.1% |

| Oct-08 | 969 | -16.9% | -7.5% | 15.6% |

| Aug-98 | 957 | -14.6% | 6.2% | 29.8% |

| Dec-18 | 2417 | -12.4% | ||

| Sep-74 | 64 | -11.9% | 16.3% | 13.5% |

| Nov-73 | 96 | -11.4% | 1.7% | -28.3% |

| Sep-02 | 815 | -11.0% | 8.6% | 12.4% |

| Feb-09 | 735 | -11.0% | 8.5% | 38.4% |

| Mar-80 | 102 | -10.2% | 4.1% | 28.0% |

| Aug-90 | 323 | -9.4% | -5.1% | 29.2% |

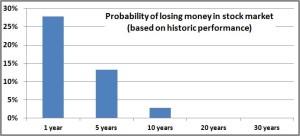

Who knows what will happen in January 2019 or the next 12 months, much less the next week (I certainly don’t). Yet if you use history as a guide, there’s a lot of reason for optimism.

Of the 9 months that made the top 10 that we have data on, 6 of those 9 month saw gains in the stock market the next month. I would definitely take an even-money bet that January 2019 will be a up month. But by no means is it a sure thing; look at Oct-87 and Oct-08, the two worst months. Those were followed up by brutal months.

Things look even better if you push the time horizon out from one month to a year. For those 9 really bad months, if you looked at the market a year later, things looked good, really good. 8 of those 9 examples saw the market up, and all of those up years were up double digits. They made up for the bad month and then some. Of course, November 1973 shows you that’s not a certainty, but the fact that almost 90% the time things recover fully makes me feel pretty good.

What’s going to happen?

As I was doing the research for this post, I was struck by the examples of those really bad months. Some of them are explainable while others are a bit odd. October 1987 was Black Monday; October 2008 and February 2009 were the Great Recession; September 2002 was the popping of the Dot Com bubble;and November 1973, September 1974, and March 1980 were all a part of the Stagflation lost decade of the Nixon and Carter debacles.

Those others are a bit odd in that there really wasn’t a powerful reason that has survived the test of time. I am sure you could look it up, but off-hand I couldn’t tell you what happened in August 1998 or August 1990. Things were going well and as you can clearly see, a year later that bad month was a distant blot in the rear-view mirror.

I feel like that is what we’ll think of for December 2018. By all measures things are going well for the economy. The economy seems to be growing well, unemployment is low, and inflation is tame (between 2-3%). Those are generally the Big 3 that you look at to see how things are doing, and they all seem okay or even better than okay.

That’s not to say there aren’t risks. Of course there are, but there always are. Brexit seems like it will have a rocky landing, the trade war between the US and China looms large, Trump pulling troops out of Syria might destabilizing, sovereign debt continues to pile up, and on and on and on. That’s true now but there were other “risks” you could have sighted for any of those other Top-10 bad months. I don’t think things are particularly worse now.

As always, I am optimistic about the stock market. I think this month will be similar to August 1998 or August 1990 in that the statistics show it was a bad month, but people can’t really tell you much about it because it was in the midst of good times.

That said, I do think there is the potential that we might be in for a couple lean years, maybe of the +/- 5% variety. Over the past 5 years, since 2013, the market is up 70%, so it doesn’t seem unreasonable that we’re “due” for a bad year or two.