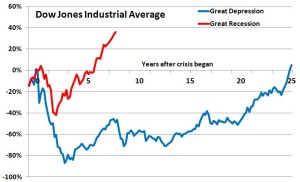

I’ve done a ton of posts on how over time stocks are a great investment, and I absolutely believe that. However, like with all things, if you look at the extremes you start to see funny results. Particularly, over the very short term, stocks aren’t really good investments at all. In fact, if you “invest” in stocks and have a really short time horizon, you aren’t investing at all but rather you are gambling. So investing or gambling, what’s the difference? And when does stock ownership switch from gambling to investing?

As always, this is when I nerd out and get my handy dandy computer and free data from the internet and see what the numbers say. Hopefully it’s not surprising that the longer you hold on to an investment, the lower the probability that you lose money. But it is interesting how the numbers work out.

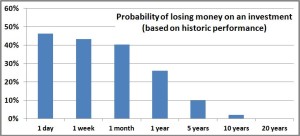

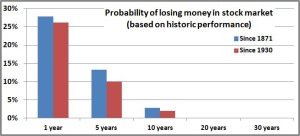

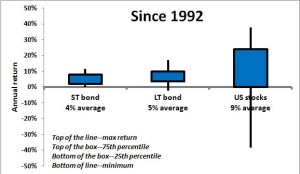

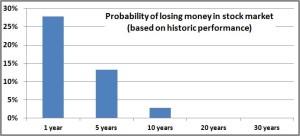

On any given day, there is a 46% chance that stocks will go down. That’s not quite a flip of the coin (since stocks go up over the long run, you’d expect them to have more good days than bad), but that’s pretty darn close. So let’s agree that if you’re investing for only a day, then you’re gambling.

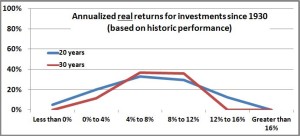

Obviously, you can contrast that with the other end of the spectrum where historically there hasn’t been a 20 year period where you would have lost money. 0% chance of losing is not gambling, that’s clearly investing.

So where do you draw the line? If you move from a day to a week, the chances of you losing money drop from 46% to 43%. That’s a little better, but that still feels like a flip of the coin to me. Go from a week to a month, and the chances of you losing money drop a little bit more, down to 40%. It’s going in the direction that you would expect—probability of losing money drops the longer you hold on to the investment—but we’re still squarely in gambling territory. If you do something and there’s a 40% chance of it coming out bad, I definitely don’t like those odds.

You can follow the table and see that at 5 years, the chances of you losing money on stocks is about 10% and at 10 years it’s at about 2%. Clearly there is no right answer, and this is an opinion question so everyone is different, but I figure that somewhere between 5 and 10 years is when purchasing stocks ceases to be a gamble and starts being an investment.

Recreational investing

One of the things I try to do with this blog is help people better understand the stock market and how it behaves by looking at historic data. I think this is a good example.

As I said at the start, the stock market is a great place to build wealth but you have to be smart about it and you have to have your eyes wide open. If you’re investing just for a month or a week or a day, just understand that what you’re doing looks a lot less like investing and a lot more like gambling. If that’s what you want to do that’s great. Just be honest with yourself.

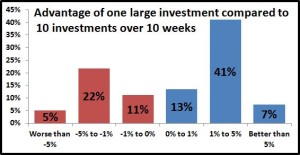

This brings me to an interesting topic which is “recreational investing”. A lot of people come up to me and say they understand that slow and steady, and index mutual funds, and a long-term view are probably the best way to build wealth. But it’s boring (a sentiment I totally agree with), and they want to keep a small portion of their money so they can “play,” investing in particular stocks they like, similar to the way someone would pick a horse at the track or play the table games in Vegas. To this I say: “go for it”.

Life is too short, and that stuff can be really fun. If it’s fun for you to “play the market” and gamble on some stocks, rock on. Just know that you’re gambling and not investing. But I’ll tell you, if you have a gambling bug, I’d much rather do it with stocks than blackjack or the ponies. With stocks, as we saw above, even over a short time frame, you have the “house advantage”. With other types of gambling, the house has the edge. So I totally support recreational investing if that’s what you’re in to.

What do you think? At what point does buying stocks change from gambling to investing? I’d love to hear.