Holy crap!?!?!? Did I just say college is a waste of money?

The very idea seems anathema to everything our society has drilled into us. Education is the best investment you can make. College allows the poor but smart to have access to lucrative job markets, allowing for incredible social mobility. Broad access to college is often credited for many of the amazing advances in our society over the past century.

However, this is also one of the most stressful areas of personal finance. Whenever I work with a someone on their finances I always ask what their goals are. Nearly universally, it is to pay for their kids’ college educations and to retire comfortably. Paying for college is a primary goal and a huge expense which causes an incredible amount of stress.

A good rule of thumb I tell people is that you’ll need to save about $500 per month to pay for a child’s college education starting when the child’s a baby. That’s for a state school, so if you want to pay for private school the number is closer to $1,500 per month, PER CHILD. A family with a couple children could easily need to save a few thousand dollars a month. That, ladies and gentlemen, is real money. Given the huge investment we’re talking about, it seems worthwhile to ask the question: Is college worth all that money?

On a personal level, I got my bachelor’s degree in finance from the University of Pittsburgh and my master’s degree in business from the University of Chicago. That education played an essential role in allowing me to make a very comfortable income to the point that I was able to retire in my mid-30s.

For our own cubs, Foxy Lady and I save $1,000 each month in their 529s which will one day go to pay for their college educations. When the time comes we think we’ll have about $400,000ish total combined for both of them. That will allow us to pay for each of them to go to a state school (think University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill) with some left over, or for each of them to go to a private school (think Harvard) but they’ll need to take some loans. Based on that, you can decide if I am eating my own cooking here.

So what gives? Why would I even ask such a seemingly self-evident question?

College is expensive

College is expensive, but that doesn’t mean it’s not worth it. There are a lot of things that are expensive but are totally worth it.

The key question for college is does the increased income available because you can get a better job thanks to your degree offset the cost of attendance. In that way, it becomes a pretty simple calculation.

Fortunately, because this is such an important issue in society, there’s actually a lot of data out there to help us with this calculation. Unfortunately, because this is such a politically and socially charged issue, a lot of people misanalyze this data to achieve their own agendas. The goal of this post is to get to the bottom of it all in as objective a way as possible.

This table shows how much college costs.

|

Total cost of attendance per year |

|

| Typical public college (UNC, UCLA, Michigan, etc.) | |

| Typical private college (Wake Forest, Harvard, Stanford, etc.) |

This table shows the average income for people with different levels of education. There are some real problems with this table that we’ll discuss probably in the next post, but let’s start with this.

| Education level |

Average income |

| High school dropout |

$26,200 |

| High school degree |

$36,000 |

| College degree |

$60,000 |

| Graduate degree |

$71,800 |

| Professional degree (doctor, lawyer, etc.) |

$90,700 |

The race of the fast versus the smart

We’re going to use my cousins Smarty Fox and Fasty Fox on this one. They are twins, identical in every way—they are equally smart, equally hard working, equally ambitious, equally anything that would impact their career prospects. The only difference is that Smarty decides to go to college while Fasty decides to start working right after high school.

Also, Smarty’s and Fasty’s parents saved enough for both cubs to go to a private college ($280,000 for each cub). They’ll use that to pay for Smarty’s education. For Fasty, they will put the $280,000 into a trust that will invest that money in the stock market and be available in her later adulthood (the comparison we’ll do doesn’t really require that Fasty and Smarty have that money upfront in a college fund, just that Smarty pays it and Fasty doesn’t). Let’s compare who ends up with more at the end of their careers.

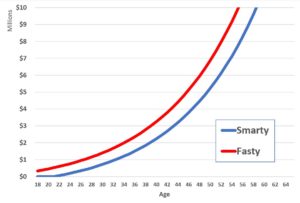

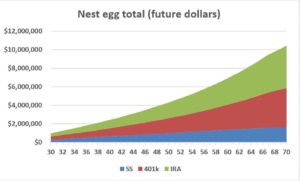

As you would expect, Fasty starts with a huge lead. First, she invests the $280,000 her parents had saved for her college. We know, especially over a long time horizon, she’s virtually guaranteed to make money in the stock market. Second, that $280,000 is growing each year; if we use an average return of 7%, in her first year she gets about $19,600 which her studious twin doesn’t get. Third, Fasty starts working right out of high school; in her first year she makes $36,000 while her twin doesn’t make anything.

For the first four years of her career Fasty builds her lead with the salary from her job and the returns from her $280,000. After four years, Fasty has about $525,000 while Smarty is starting at $0. However, Smarty has a degree and can get a job at a much higher salary than her twin. Smarty’s first job pays $60,000 which obviously is much more than the $36,000 Fasty is making.

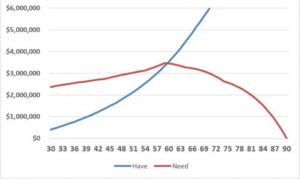

Fasty has that head start but Smarty has the higher income. Which will prevail?

As it turns out, it’s not even close. Fasty’s lead is just too big for Smarty to catch up. Smarty will be making about $24,000 more each year than Fasty, which seems like a lot. However, Fasty’s $525,000 lead allows her to earn an investment return of about $37,000. That more than offsets Smarty’s higher salary. By the time Fasty and Smarty have reached 65, Fasty will be MILLIONS ahead of Smarty.

So there you have it. Don’t go to college. Just invest the money and you’ll come out ahead. But . . .

Is college education really a rip-off?

This is a tough one. I’ll go back to how I started this post. College is such an integrated part of our lives and society. Colleges also have historically been universally revered—these are good places, doing good work, making the world a better place. But maybe those are the very places where we should question that absolute goodness.

From a purely financial point of view, college may not be worth it. Hold on though; I’ll beat you to the punch and say all the things this quick analysis didn’t factor: college major, drop-out rate, intelligence of person, future educational options, income growth, and taxes just to name a few. Tune in on Wednesday when we’ll go over that.

The other big thing this post missed is all the non-financial elements of college. College might be a time to spread your wings and discover yourself. There are so many opportunities to pursue so many interests, many of which you may never have known you had. You’ll make lifelong friends and maybe even your life partner (as was the case for me and Foxy Lady in grad school). Of course, I’m not sure that college, and it’s really high costs, is the only place you can get those experiences.

Also, life isn’t always about money. This is a personal finance blog so that’s what we tend to look at, but that doesn’t mean every decision needs to be based on money. That said, this becomes a bit philosophical. What is the purpose of college? My view is those non-financial things are nice-to-haves compared to college’s ultimate purpose of preparing young people for gainful employment so they can become self-sufficient and contributing members of society.

Complex stuff. Tune in on Wednesday for part 2.