“I drink two kinds of beer—free and Budweiser”—millionaire interviewed in book

The Millionaire Next Door definitely deserves a place near the top of any list of books on personal finance. Its two authors, Thomas Stanley and William Danko, were two professors who undertook a massive study of America’s millionaires to figure out what made them tick. How did they get rich? How did they stay rich? And generally, what are their views on money?

Reading this is almost like watching an archaeological documentary on PBS with Will Lyman narrating: “Americanis Millionairo is a subspecies whose prodigious wealth-building abilities have been studied for centuries.” Basically, the authors conducted thousands of interviews with millionaires and asked them questions on nearly every subject of personal finance, and the book is those survey results. Nearly every aspect of millionaires is examined to find common themes—working income, country of origin, education, divorce status, occupation, Rolex-ownership, and a hundred others.

Distilled down to its simplest, the book reaches two conclusions which are really opposite sides of the same coin:

- Frugal spending habits are the single biggest factor to being able to become a millionaire.

- Flashy spending occurs among a small minority of millionaires, and in fact flashy spending tends to be a major factor to not becoming a millionaire.

For those aspiring to be millionaires it’s a wonderful how-to guide on becoming rich the slow-but-steady (and boring) way of spending less than you earn, making luxuries an special indulgence instead of a daily staple, and generally have a grounded view on life and expenditures. It’s analysis shows that most millionaires get that way by prudent spending and diligent saving; not by having jobs that pay million dollar salaries, not by inheriting the money from rich relatives, and not by “hitting it big” in some venture. It’s this element of the book that is most powerful—it democratizes millionairehood (I just made that word up).

For those who are already millionaires and became so by leading a life with “sensible spending”, I think it provides comfort that they aren’t alone. Our society is bombarded with images of what “rich” people should look and act like. In the 1980s shows like Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous (I must confess a favorite of mine as a kid) celebrated the over-the-top extravagance of the wealthy. That tradition has continued with a myriad of shows like Platinum Weddings (a favorite of Foxy Lady) and Million Dollar Rooms to name just two. However, the book does a tremendous job of breaking through those stereotypes to show that the vast majority of America’s wealthy are just normal people who spend their money sensibly or even frugally.

In true academic fashion (one of my criticisms of the book is that is reads more like a research paper than a bestseller, but it is a best seller, so what do I know?) the authors break down pretty much every demographic element of millionaires and just as interestingly, those people who make a bunch of money but aren’t millionaires. Some of the findings are obvious like there are a lot of millionaires who started their own business. But others are make a ton of sense but wouldn’t have been top of mind as such a determining factor; an example of that is divorce which the authors describe as a millionaire killer (Foxy Lady—have I told you how much I love you?).

They slice and dice things and thousand different ways. What do you want to know about your average millionaire? Average age of car (2-3 years), percentage self-made (80%), attended public schools (55%), ancestry (Russian followed by Scottish), percentage who have a JCPenney card (30%), and on and on.

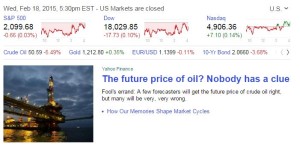

Of course, I look at these things through an investing lens, and I was a bit disappointed that the authors spent so little time on this subject. In a book with almost 300 pages, only about 4 or 5 are dedicated to what millionaires do when investing their money. And this seems like a major gap considering that investing can be as responsible for building wealth as earning the money in the first place. They cover the most the millionaires have paid for a suit, a watch, a pair of shoes; but they don’t talk about what type of investments they make? Seems weird.

The three major takeaways about investing you get from the book are:

- About 80% of millionaires do invest in stocks and other securities. This seems obvious, and actually a little low. What are the other 20% doing.

- Most use a “buy-and-hold” investing strategy as opposed to actively and frequently trading stocks. I’m glad to see this (this is a topic for another blog post).

- Considerable time is spent discussing how millionaires go about hiring a financial advisor.

If I had my way I would have loved the authors to really dive in here. If you believe that the point of the authors writing this book is to show the masses how they can become millionaires (and I believe that to be true), then after they adopt the “frugal” spending habits, then it becomes important to know what to do with the money after they’ve saved it. Here is my list of a few questions I would have loved to know: What percentage use a financial advisor versus do it themselves? Do they tend to invest in individual stocks or mutual funds? How much of their portfolio is in stocks versus bonds?

Overall, the book reads a little stiff, and at some times it gets preachy (especially the section on how to discuss money matters with your kids) so that’s a bit of a turn off. Also, it was written in 1999 and because of that there are a lot of areas that are quite dated and don’t really apply to the world 2015. But it does provide tremendous insights into their everyday activities of these people and how those have help them accumulate so much wealth. For all that it gets 2 ½ stocky foxes.

As a closing note, I want to thank my coworker who gave me this book as a Christmas gift back in 1999. You know how you are, and I hope you know how much I enjoyed reading this.