I’m trying to build my audience, so if you like this post, please share it on social media using the buttons right above.

Here’s a question that I received from a reader the other day:

Stocky—my 26-year-old son has saved about $20,000. Right now it’s just sitting in his checking account. What should he do with it?

–AK

The first thing is to ask if he “needs” that money for anything in the short-term. Does he need to buy a car, or is he going to buy a house and use that as a down-payment, or something?

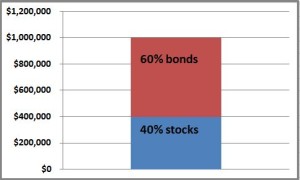

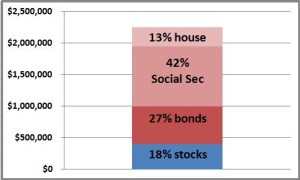

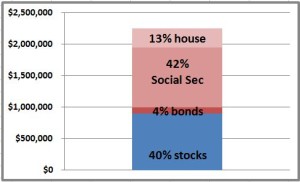

If the answer to that is “yes”, then he can open an account with Vanguard or Fidelity, and invest the money in a broad bond fund like VBLTX or BND. That will provide a decent return (about 3-4%). Of course, there’s a chance that he could lose money, but based on historical data the chances of that are pretty low, and if he did lose money it wouldn’t be a huge percentage of his investment. This isn’t like stocks.

Investing for the long-term

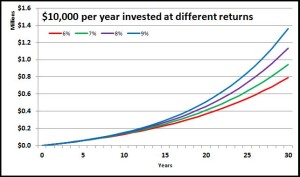

Now let’s get to the more interesting stuff. Let’s assume that the $20k is just hard-earned savings that can be invested for the long-term.

401k—The very first place I would start is with his 401k if he has one at work. Hopefully, he is already contributing to that at some level, and this $20k is on top of that. The max you can contribute to your 401k in 2019 is $19,000.

With a 401k you can’t really take the $20k he has saved and put it directly into the account, so we have to do it in a bit of a two-step process.

Let’s say in his normal budget he is able to contribute $200 per paycheck into his 401k (that comes to $5200 per year). That means that he could contribute $13,800 more.

Crank the percentage up as high as it will go (usually something like 50%), and that will accelerate his contributions until it hits $19k for the year. Then the law forces the contributions to stop.

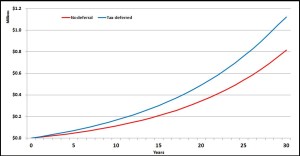

That will greatly reduce his paycheck, but then that’s where the $20k he saved comes in. He can use the $20k he saved to replace the big chunk of his paycheck that went to his 401k. Actually, since 401k contributions are pre-tax he’ll actually only need to take $11k or so to replace the extra $13,800 he is adding to his 401k.

If he has $20k in the bank he could do this for about 2 years. Just remember that when his $20k runs out to set the 401k contribution percentage back to a normal level.

As far as investments go, a 401k is meant to be a long-term investment so I would make sure he is invested in some type of broad stock index fund.

IRA—If he doesn’t have a 401k or even if he does, he should open an IRA. He can do this at any brokerage, but I would suggest Vanguard or Fidelity.

Here he can contribute directly to an IRA (instead of the two-step process for a 401k). Once his IRA is open he can contribute up to a limit of $6000. Just like with the 401k, this money is meant for the long-term, so I would invest it in a stock index fund.

As he opens his IRA account he’ll also need to decide if he wants to do so with a Roth IRA or a traditional IRA. I have written extensively on this, and generally his choice should be a traditional IRA (unless his income this year is very low—let’s say below $30k).

After he’s made his $6k contribution ,that will mean that he’ll have a lot left over. That takes us to a normal brokerage account.

Brokerage—These are similar to IRAs but without the special tax treatment or contribution limits. You can open these up at the same place as you do your IRA. So if you open your IRA up at Vanguard, I would keep it all in the family and open your brokerage account at Vanguard as well.

Once you have contributed to your 401k and IRA for the year, you can put the rest in that same stock index fund. Next year, especially if he’s going the IRA path, he can just transfer the money from the brokerage mutual fund to the IRA mutual fund and it’s all easy. Of course, there may be tax implications for this, but that’s one of the reasons why you want to get the money tucked away in a 401k or IRA as fast as you can.

I hope this helps. Congrats to your son for having suck a strong head start. Now that he’ll have that money invested, it will be turbo-charged.