As you might imagine, I talk to a lot of people about what they’re doing with their investments. One of the things I hear a lot is, “I’d like to start investing, but before I do that, I need to build up my emergency fund.” That sounds pretty prudent. You don’t want to get caught in the lurch when life throws a curve ball at you. Yet, I actually think this is a really bad move. I freely admit that the Fox family does not have an emergency fund. We have investments, and if the unforeseen happens that’s what we’ll use.

How likely is an emergency?

What are the types of things that you’d use an emergency fund for? Almost by definition, an emergency is something that is unpredictable and somewhat rare. If your 12-year-old Honda Civic is starting to die and you know in the next couple years you need to get a new one, that isn’t really an emergency as much as something you need to budget for (that was the exact circumstance of the Fox family a few years back). If you’re having an “emergency” every year, either you’re the unluckiest of people, or probably more likely you just have a lifestyle that needs to be budgeted a little differently.

When I think of things that you’d spend an emergency fund on it’s stuff like: your hot water heater gives out, you’re 7-year car gets totaled and insurance only gives you $6000 to get a new one, your son goes into the NICU for four days because of croup and your portion of the bill is $4000 (as happened with Lil’ Fox last year), or you are fired from your job.

As I was writing this post, I asked Foxy Lady if she could remember any emergencies that we have faced since we were married 7 years ago. The hospital thing with Lil’ Fox was the only one we came up with. There were smaller things like when we had to replace the dishwasher ($500) or fix the clothes dryer ($400), or fly back to Michigan for a funeral ($400), but the hospital thing was the only major one (I’m defining “major” as more than $1000). So that means we have averaged one emergency every several years. Once every several years—I don’t know if we’re more or less prone to emergencies than the general population, but that seems about right.

So be a little more cautious and use once every five years as an average—you have about a 20% chance in any given year of needing to tap into your emergency fund. We’ll use that in a second.

How likely is it you’ll make money in the stock market?

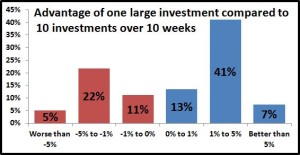

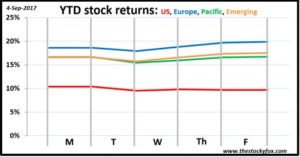

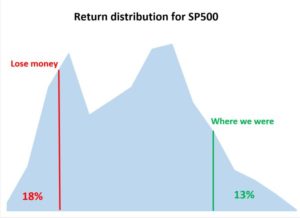

Obviously we put a huge caveat on this, but we can look at historical performance to get a sense for how likely it is that you’ll make money or lose money if you invest your emergency fund in stocks. Actually, we kind of did this in a post a while back.

Remember that historically, if you have a one-year investment time horizon, you make money with stocks about 70% of the time. That is actually pretty good odds that investing your emergency fund in stocks would have you come out ahead, just looking at it for one year. In fact, we can do the math, and the chances of you having an emergency in a given year and losing money in the market are about 6% (20% chance you’ll have an emergency x 30% chance you’ll lose money in the market that year).

But remember, emergencies don’t happen every year—they tend to be much less frequent than that. For the Fox family, they happen on average once every five years. Just for the fun of it I put a table together that estimated the chances of having an emergency if you assume in any given years there’s a 20% chance of having one. Also, I looked at the historic data to see the probability that you would have lost money in the market over different time horizons.

| Time horizon | Chance of an emergency | Chance of losing money in stock market* | Chance of emergency and losing money |

| 1 year | 20% | 28% | 6% |

| 2 years | 36% | 24% | 9% |

| 3 years | 49% | 18% | 9% |

| 5 years | 67% | 13% | 9% |

| 10 years | 89% | 3% | 3% |

As we mentioned above, there’s a 6% chance that in any given year you would need to tap your emergency fund when the market was down. Looking at other time frames you get similar results. Pretty much any time frame has a less than 10% chance of you needing that emergency money at a time that you would have lost money in the market*. You need to decide if you’re willing to take that risk, but to me that seems like a no-brainer. If I have a 90%+ chance of coming out ahead on something, I’m doing it.

You can see where I’m going with this. First, emergencies don’t happen all that often (if they do, you probably need to come up with another name for them other than “emergency”). Second, if you give yourself a few years in the stock market, the probability of losing money goes down a lot (of course, it never goes to zero). That seems like a perfect combination for investing your emergency fund the same way you invest any of your other money. $10,000 invested in stocks with an average return of 6% would give you about $13,300 after five years; keeping that same amount if your savings account at today’s interest rates would give you about $10,050. Seriously, that’s ridiculous.

I get that many people look at that and say, “the whole point of an emergency fund is you never know when you’ll need it, so don’t put the money somewhere where you might lose it.” That’s a very understandable concern, but it’s also where a lot of people are leaving a ton of money on the table. Over the past 150 years, investing in stocks has a really good track record, and the more time you give it, the better that track record becomes. You’ll never eliminate all the risk from investing, whether it’s your 401k or US bonds or the cash in your checking account, there will always be some type of risk.

It’s the successful investors who understand that risk and understand how to decrease the risk (expanding that time horizon to five years cuts in half the likelihood of losing money), that are able to get the most bang for their buck. This is definitely one of those areas where you can get a 1% coupon.

The Fox family eats on our cooking on this one. We don’t have an emergency fund. When emergencies do happen like with Lil’ Fox, we pay for it out of our investments, absolutely believing that over our lifetimes there may be one or two instances where we lose money but there will be many, many more where we come out ahead.

Let me know what you think. Do you have an emergency fund? Do you think I’m crazy not to have one?

*I used the same methodology for this table that I did for my post “Will you lose money with stocks?”