The Top 5 ways changing your own oil is like doing your own investments

Just the other day, I changed the oil in our 4Runner and our Honda. It was the first time in my life I ever did that by myself instead of taking it to a dealership or one of those quick lube places. First, I want to thank my new BFF Jesse Bearcat for helping me.

Second, as I was doing that and since, I have started to think how changing your own oil is a lot like doing your own investing. In fact, a lot of the benefits of doing an oil change yourself are exactly the same as doing your investing yourself.

Here are my Top 5:

More conscientious: No one cares more about you and your wellbeing than you. Twice in my life I have had horror stories of the guy at the shop doing a crappy job and it leading to bad, bad results. They were sloppy and forgot to connect a hose which led to my car breaking down and needing a tow. Once I was driving on the road into the LINCOLN FREAKIN’ TUNNEL.

When I do the work on my own car, the car that hauls around my family, you can be sure that I check and double-check every screw and tube and everything. Investing is the same. Is someone else going to check the next day to make sure your fund transfer happened or that the change in your 401k allocation took?

Better materials/parts: I buy name-brand oil and filters. I don’t know if they are better than the discount stuff those quick-lube places use (normally I am a big fan of generics, but motor oil seems a little different). It’s an open question. At a quick lube place I never used synthetic oil because it was an extra $30 or so, and I’m too cheap for that. When I do it myself, 5-quarts of oil costs about $3 more when you buy synthetic, so that’s a no-brainer.

Similarly with investing, when you do it yourself you can pick the best mutual funds at the lowest price. I have spent a ton of time on why I think index funds with a low management fee are the best. When you do it yourself, you can pick anything you want. When someone else does it for you, your choices tend to be more limited.

Better use of your time: This is a bit counter-intuitive, but it’s absolutely true. When you change your own oil or do your own investing, you actually save a lot of time. To change your own oil, you take 5 minutes to set everything up, 1 minute to unscrew the oil plug, and 1 minute to unscrew the oil filter. Then you let the car drain for 10 minutes or so while you’re doing something else. You can come back, screw the new oil filter on (30 seconds), screw the drain plug in (30 seconds), fill the oil and check the levels (5 minutes).

If you go to a place it might take you 10 minutes to drive there, 10 minutes waiting time, 20 minutes for them to do it while you’re stuck in the car. Doing it yourself saves a lot of time.

Investing is the same way. If you have your investment advisor do it all, you still need to meet him, drive to his office or schedule a call, etc. You can do it on your own at night in your pajamas after the kids have gone to bed while the World Series is on in the back ground. I know which one I would choose.

Look at other things: As I have started doing my own oil changes, I am becoming more knowledgeable and look at other things about my car as well. When I went to a place to get my oil changed, they always say I need extra stuff down, and I totally shut them down because I think they’re just trying to fleece me (good analogy to personal finance there). However, there are other maintenance things you need to do to your car.

Changing the air filter is one of those. The oil change place says I always need to do it, and I actually do it every once in a while. Now that I change my own oil, I have the confidence to check that and it’s surprisingly easy. I can do it in 2 minutes (plus get a good price on the filter from amazon.com which is maybe 80% less than what they charge me).

Investing is the same. It’s easy for an “expert” to come at you and tell you all the things you need to do. It’s natural to resist that a little, knowing a lot of it you don’t need to do, but some of it you probably should do. As you get more knowledgeable, you’ll know what does make sense (probably an IRA) and what doesn’t (probably an annuity). That can pay HUGE dividends (figuratively and literally).

Lower cost: It costs $40-60 to change our oil at one of those quick lube places, plus a lot more if they did my air filter and other stuff. It’s much higher at a dealership. My all-in cost for an oil filter and 5-quarts of synthetic oil are probably about $20.

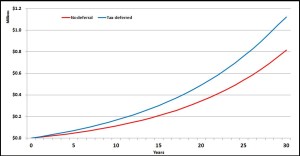

Those are decent numbers for a car, but you know how that translates to your personal finances. If you do investing yourself, you can save a boatload in costs and fees that would line the pockets of investment advisors, mutual fund companies, and everyone in between.