I’m trying to build my audience, so if you like this post, please share it on social media using the buttons right above.

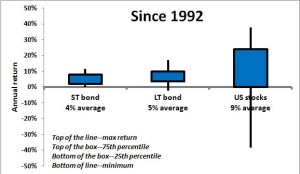

Last week I said that savings accounts were for suckers, and that instead you could use bonds to accomplish pretty much the same thing, but make a lot more in interest. A couple readers asked how that worked in a little more detail.

“Hey thanks for the finance blog… What bond funds do you recommend (ETFs) and do you just hold them in a normal brokerage acct to be able to sell them?” –JS

“How liquid are Bonds? Say I need a quick 5K for a new HVAC unit or some other unforeseen expense. Should I keep any money in a traditional savings account?” –CW

If we like the concept of using bonds instead of a savings account, let’s dive into how we would actually do it.

1. Open a brokerage account with Vanguard (or Fidelity—we have money at both, but more at Vanguard and have been with Vanguard longer. Both are excellent. I’ll write this for Vanguard but in parenthesis I’ll put the information for Fidelity). You want to make sure it’s a regular brokerage account and not an IRA or something like that.

As a “savings account” you’ll want be able to pull out money when you need it. A brokerage account allows you to do that, but an IRA account would not.

2. Link your Vanguard account to your checking account. This is very secure and I have never had an issue with it.

Online you’ll put in your checking account routing number and account number. A few days later you’ll see two little deposits (think something like $0.21 and $0.09). This allows Vanguard to ensure that it’s your account. When you see those amounts, you’ll go back to Vanguard’s website and enter them.

Once you’ve confirmed those, then you’re Vanguard account will be linked to your checking account, so you can transfer money between them very easily. Sadly, there’s no free lunch and Vanguard will take those two little deposits back.

3. Pick your bond fund. Vanguard has a ton of options (as does Fidelity). I want to keep it simple so I pick an index fund to minimize fees. Also, I want to go as broad as possible to maximize diversification. Basically, you can go one of two ways—either buy a bond ETF like BND or buy a bond mutual fund like VBTLX (for Fidelity it’s FXNAX).

ETFs are a lot more flexible and I think we’re entering a world where mutual funds will slowly go extinct in favor of ETFs.

4. Buy your BND shares. Take what ever was in your savings account and buy shares of BND. It’s a pretty easy process. Depending on how much money we’re talking about, you might want to break it up into a couple purchases, although statistics say you should just dive in with a single purchase.

5. When you go to buy the shares, it will ask you how you want to fund them. You’ll pick your bank account that you just linked and it will all work.

When you need to take money out of your savings account (like when CW’s heater goes bad), you just do the opposite—sell the shares and when it asks where you want the money you select your checking account. Generally it takes about two or so business days to complete the transaction, so just make sure you plan a little ahead.

These ETFs are extremely liquid so you can sell them whenever the market is open. In fact, you can also sell or buy them when the market is closed. It will just fill the transaction at the next possible price, when the markets open next.

Easy peasy, lemon squeezy.