It’s time for the mailbag again. Thank you to everyone who reads the blog, and a special thank you to those who have emailed me questions. I enjoy seeing the questions my readers have and doing my best to answer them. If you have any questions about investing, please send them to me in a comment or email and I’ll be happy to include them in a future mailbag.

So without further adieu, here are actual questions from actual readers:

How do you allocate your investable funds across taxable and tax-deferred accounts?

–Aaron from Ft Wayne, IN

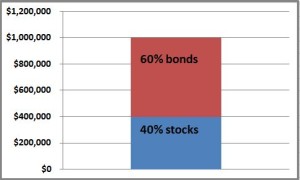

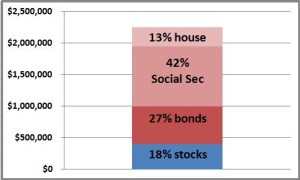

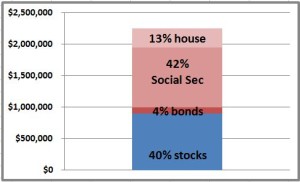

First, remember that tax-deferred accounts tie up your money for quite a while—until you’re in your 50s at least. So you have a longer time horizon, and the investments that best match a longer time horizon are stocks.

Also, tax-deferred accounts are most valuable earlier in your investing career (because you defer the taxes for longer). If you’re a younger investor then you should definitely have most, if not all, of your money in stocks just because of asset allocation. So those two conspire to tell you that stocks are probably the best bet for tax deferred accounts.

If you do decide to have bonds as a part of your portfolio then those probably make more sense to be in your taxable account just because that’s the money you want to be able to access if you need it in a hurry. Unfortunately, the tax treatment won’t be great because bonds tend to have higher yields than stocks so you will be taxed on those.

A final thought—if your entire portfolio is mostly stocks (as is the case with the Fox family), you can get a little creative with which stocks you put in taxable accounts and which in tax-deferred accounts. The logic is you would want to put the higher-yield stocks in a tax deferred account because you want to delay when you pay those taxes. For the Fox family, most of our money is in a US stock mutual fund (VTSAX) which has a dividend yield of about 1.8%, and an International stock mutual fund (VTIAX) which has a yield of 2.7%. All other things being equal, we should have our international mutual fund in the tax-deferred accounts because of the higher dividend. The tax savings aren’t going to change the world, but I would bet that over the course of an investing career, it would add up to maybe $10,000.

How to invest short term in a zero interest rate environment? (i.e. we’re buying a house within a year or two but not for certain yet – how to invest the down payment until then?)

— Noah from Chicago

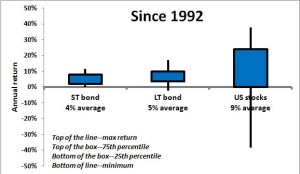

There’s never a free lunch, so if you’re looking for a higher return you need to be willing to take on more risk. If your time horizon is a year or two, I think you would be pretty safe with a short-term bond fund (like VSGBX). In the past few years the return has been about 1.5% which isn’t very good. But the chances of you losing your initial investment are pretty low. So you have some upside with pretty limited downside.

If you’re a little braver, maybe you go to a bond fund with longer maturities (VBMFX). The return the past few years has been in the 4% range so that’s quite a bit better, but of course there’s a greater chance that you might lose some of your investment.

Having said that, there’s a double challenge with investing in bonds right now. First, current yields are super low (as you mentioned) so you aren’t making a lot on them. Second, eventually interests will rise and when they do, that will lower the prices of your bonds. So it’s tough to say. However, those two factors have been in place for at least 5 years, and long-term bonds have yielded 4% over that time, so who knows.

I would definitely not recommend stocks. Everyone says that the market is overvalued (but who knows really). However, stocks in general can take a 10% dive in the blink of an eye, and if you need that money in the next couple years to buy a house, I just don’t think it’s worth the risk.

Good luck and happy home hunting.

What about bitcoins? Any room for them in the portfolio?

–John

Bitcoins have definitely captured the imagination of the financial markets. Let’s break this question down into two parts:

Investing in foreign currencies as a strategy—Since bitcoins are really just a different currency, let’s look at this broadly. When Foxy Lady and I started investing in commodities, we also thought about investing in foreign currencies as well (I’m glad we didn’t because then we would have another investing disaster on our hands).

Similar to commodities, investing in foreign currencies isn’t generating value the way investing in a company does. With currency trading, you’re just betting that the euro or franc or yuan will do better than the dollar. Notice I used the word “bet” instead of “invest”. When you trade commodities, it’s a zero-sum game so if you make money that means someone else on the other side of that trade loses money. That’s just a game that I don’t feel qualified to play.

Also, if you are broadly diversified, you have exposure to foreign currencies with all the stocks you own since many of those companies are doing business in those different countries. So if they do appreciate against the dollar, then you have those benefits. That’s how I “invest” in foreign currencies.

All that said, if you have some special circumstance where you do business in a foreign country (or own a property there, or have some other connection) it might make sense to invest in foreign currencies as a hedge, but that’s really a different animal.

Bitcoins in particular—I think bitcoins are a super-cool innovation, and I like reading about the crazy moves they make. I also think that something like bitcoin will have a real place in our world in the coming years.

A lot of people don’t realize that money and currency has evolved tremendously over time. Obviously it started with precious metal coins, and those gave way to paper money backed by precious metals. In the United States, it wasn’t until the 1860s that there was a uniform national currency; before that individual banks could circulate their own notes. Then in the 1930s the US went off the gold standard so paper money became a fiat currency. In the 1950s credit cards opened up a world of virtual money which has grown to the point where today I would guess 99% of your transactions are cashless. My point is: Money is constantly evolving.

So I do believe that in the future something like bitcoin might really gain traction. However, I doubt it will specifically be bitcoin. Just like social media (Facebook wasn’t the first) or MP3 players (iPods weren’t the first), I think there will be a few false starts before something really takes hold.

I like to think I’m pretty savvy with this stuff, and I don’t completely understand how bitcoins work or how I would open an account. And it seems every six months or so there is a news story about how the bitcoin infrastructure is breaking down (here and here and here). I would recommend you just grind out strong returns using tried and true methods of investing in stocks. You won’t have the chance to 10x your money the way you could with bitcoin, but you won’t risk ending up with nothing either. If you’re a gambler at heart then put a little money in bitcoin, but just be honest with yourself—you aren’t investing, you’re gambling.

How do you feel about the use of 529s?

–Aaron from Ft Wayne, IN

OMG! A second Aaron from Ft Wayne? No, it’s the same guy, just with a second question.

Absolutely, if you have kids and plan on paying for some or all of their education, 529s are a no-brainer. A 529 takes after-tax dollars and then any gains you have are tax free. In that way, they act similar to a Roth IRA, and you know how I feel about IRAs. Over the course of your child’s childhood, that tax benefit could easily reach into the tens of thousands of dollars, so that’s pretty serious money.

Of course, the negative is that if your child doesn’t use the money (doesn’t go to college, gets scholarships, etc.) then you’ll be hit with penalties. That said, the rules are pretty flexible so if your kid doesn’t use the money almost any other family member (cousins, grandchildren, brothers, sisters, even you or your wife) can use the money for educational purposes.

I totally believe in 529s. Actually, I started the ones for Lil’ Fox and Mini Fox when there were still swimming around in Foxy Lady’s belly.

Thanks for the questions and please, keep them coming.