A few days ago, a client called me a bit freaked out. He wanted to sell out of stocks because of fears that the issue with North Korea could escalate into something terrible, possibly World War III. Of course I told him to sit tight, because even in the darkest times stocks tend to do well over the long term.

Even so, what makes me so confident that the problems with North Korea won’t lead to a global catastrophe? Simply put . . . THE MARKET TOLD ME SO.

The stakes are very high

Certainly, the stakes with North Korea are very high. If things went bad, the outcomes could range from the Korean peninsula being destroyed to a nuclear war enveloping the globe.

If armed conflict broke out, almost assuredly North Korea would attack South Korea and particularly Seoul with a deadly barrage of artillery. The human cost would be immense. Also the damage to companies and their property would be vast. That doesn’t seem important when compared to all the lives that would be lost, but more on that in a minute.

If the conflict spread, Japan would probably be the next victim of North Korea before the US and its allies took control. Then the two absolute worst case scenarios would be a) North Korea realizing its nuclear-tipped ICBM dream and hitting the US mainland or b) China and Russia being drawn into a war against the US. Those last two scenarios would lead to unparalleled loss of life and destruction of company property.

Destruction is bad for the stock market

Why do I keep saying “destruction of company property?” That seems to pale in importance compared to the thousands or millions of lives that could be lost with the doomsday scenarios we’re talking about.

If war broke out a lot of company property, plant, and equipment would be destroyed. Also a lot of company employees would be killed. Potentially, if we went to a wartime economy like in World War II, companies would stop making cars and phones and shirts, and start making fighter jets, military gadgets, and uniforms.

All those things would be horrible for the companies’ profitability and therefore their stock price. Here’s the punchline—if war broke out, that would be terrible for the world’s stock markets overall. That terribleness would be most acute where the fighting was taking place.

The stock market is pretty smart

There has been a lot of academic study of the wisdom of groups over the individual. I took a class with Nick Epley at the University of Chicago that looked into this, and that’s one of the lessons that has really stuck with me over the years. The idea is that if you have a bunch of people with a bunch of different opinions, the “average” opinion is going to turn out to be more right than most of the individual opinions.

Where is the biggest, most organized collection of opinions? In the stock market. It is fundamentally people with opinions (will things be good and stocks go up, or will things be bad and stocks go down?) betting against each other. The result of all the bets results in the general movement of the stock market. If more people bet good things will happen, stocks go up. If more people bet bad things will happen, stocks go down.

Stock markets have a lot more credibility than talking heads because the former involves people putting their money where their mouth is. It’s easy to say you are certain that something is going to happen; it’s another bet your money that something is going to happen. That’s why the stock market tends to get it right, because greedy people who want to make more money are betting.

With regard to the Korean conflict, it’s easy for guests on news channels to say how bad that nuclear test is or how much closer that missile launch puts us to war. But are those concerns credible? Does the talking head or the new network really believe that, or is it just a flamboyant statement meant to capture viewer’s interest?

Divining the markets’ message

We’ve talked about geopolitics and stock markets and the destructive potential of a war with North Korea. Let’s bring it all together.

If war breaks out, a lot of destruction will occur, and that will be horrible for the stock market. That’s particularly true as you get closer to the epicenter—things will be worse for South Korean stocks since they’ll be the first victims of the war, probably followed by Japan, and then the rest of the world.

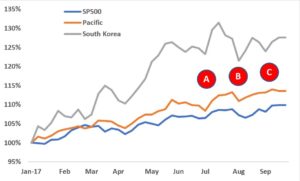

If things were REALLY bad, you should see that reflected in the stock markets, yet it isn’t. If you compare the S&P 500 and a broad Pacific Index (Japan, South Korea, Australia, etc.) and a South Korean stock index, none show signs that a horrible event is going to happen. In fact, of those three, the South Korean index has VASTLY outperformed the other two. So much for a real concern that unparalleled destruction is imminent.

That’s not to say there haven’t been reactions. In the beginning of July (point A) North Korea tested a long-range missile. South Korean and Pacific markets reacted a little (about 1-2%) and US markets were unfazed.

Later in the month, North Korea tested a second missile that put Guam within range (point B). Again, there was a reaction from the markets, this time larger and this time the US markets also reacted.

Finally, at the beginning of September, North Korea tested its largest nuclear device yet (point C). Again, all three markets reacted.

So what does it all mean? The market did react downward every time one of these tests occurred which means that more people (or more accurately more money) think there is something to be worried about. However, the shallowness of the dips show that the bad things that “are likely to happen” really aren’t that bad and are more than offset by the good things going on with companies, profits, employment, etc.

Particularly interesting is the South Korean stock market. If conflict did break out, they would be on the front line and they would suffer the most devastation. Their reaction to North Korea’s developments are the largest which makes sense. But like the rest of the world, the South Korean stock market quickly shrugs off the threat and moves on. As I mentioned earlier, the South Korean stock market has done really well this year, which must mean that they don’t view the threat of war to be that likely.

I hope this gives you comfort; it does to me. It’s not hard to get wrapped up in all this crap. Trump and Kim Jong Un certainly don’t make things calmer, and those missile tests keep flying longer and longer distances. When someone gets on CNN saying we are on the doorstep of Armageddon, it’s easy to believe it, but I think those people are full of crap.

The stock market has a powerful collective wisdom that has a really good track record of being right when individuals are dead wrong. I think looking at how the stock market has reacted to all of this, and particularly how the South Korean stock market has, should give us all some comfort.