I’m trying to build my audience, so if you like this post, please share it on social media using the buttons right above.

Today we celebrate Tax Day. Celebrate isn’t quite the best word, but let’s paint a happy face on this.

There a million things we can talk about with regard to taxes and personal finance, but let’s focus on one of the big changes that hit in 2018 that fundamentally affects a MAJOR financial decision we make—the mortgage on your house.

The major tax overhaul that passed at the end of 2017 is probably the biggest in my adult life. It puts a few tried-and-true nuggets of tax wisdom on their head, particularly how “itemized deductions” are treated, including your mortgage. Let’s dive in and see how that changes things.

Quick primer on how taxes were

Remember, I’m not an accountant, so this is my best understanding of how things were and are.

Before, you as a tax payer had to decide to take the standard deduction or itemize your deductions. You can only do one or the other, so the general idea is to do whichever is “greater”.

| Standard Deduction | 2017 | 2018 |

| Single | $6,350 | $12,000 |

| Married | $12,700 | $24,000 |

When you take the standard deduction, as the name implies, you just get to reduce your taxable income by a standard amount. In 2017, if you were a married couple, that amount was $12,700.

The alternative is to itemize your deductions. Things can certainly get complicated, but for most people your itemized deductions are your state income taxes, and if you own your own home your property taxes and the interest on your mortgage. If those three items were more than $12,700 then it made sense to itemize your deductions.

In 2017, for the Fox family, our state taxes were about $10,000, property taxes about $6,000, and interest on our mortgage about $9,000. All that adds up to about $25,000. So, it made a lot of sense for us to itemize our deductions. We got to reduce our taxable income by $25k instead of $13k. That probably saved us about $4,000 in taxes. Not bad.

Quick primer on what changed for 2018

There were a ton of changes in the new tax law (I think the actual document was well over 1000 pages—Yikes!!!). But let’s hit the highlights.

The same logic holds where as a taxpayer, you should pick whichever is greater, itemizing your deductions or taking the standard deduction. But that’s where some major changes occurred.

First, you can see that the standard deductions nearly doubled. That alone makes the number of taxpayers who would take the standard deduction much higher than before.

Looking at our situation from 2017, we had $25,000 in standard deductions while the standard deduction is $24,000. Back in 2017 it was a no-brainer, but in 2018 it became nearly a wash. But that’s just the tip of the iceberg.

The second major change is that there is a limit of how much you can deduct on your itemized deductions for state and property taxes. In 2017 there was no limit, so in our situation we were able to deduct $16,000 ($10k for state taxes and $6k for property taxes).

Now the limit is $10,000. That’s a major game changer. Using our 2017 numbers instead of deducting $16,000 for state and property taxes, we hit the limit of $10,000. Add the $9,000 for mortgage interest and we can only deduct $19,000. That is much less than the $24,000 standard deduction, so with the new tax laws, we will take the standard deduction.

Basically, for it to make sense for you to itemize your deductions, you need to have over $14,000 of interest expense on your mortgage. Just using round numbers, if your interest rate is 4% (and if it’s higher than that, you should refinance ?), that means you’d have a $350,000 mortgage. Anything less than that, and you’re better off taking the standard deduction.

How this affects your mortgage

Let’s bring this full circle, back to the headline of this post—How does all this affect your mortgage?

Remember that we have talked extensively about debt. I told you how we could have gone mortgage-free but decided not to, how we took a car loan when we didn’t need to and that was a good thing, and in general the approach we use for debt.

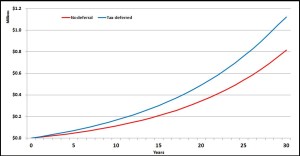

If you boil it all down, basically you should take on debt if the interest rate is really low. However, the tax change “increases” your mortgage rate because it’s not going to make sense to be able to deduct the interest.

Before if you had a 4% mortgage, after you deduct the interest on that mortgage from your taxes, it might seem more like a 2.5% to 3% rate. Obviously, that’s a big difference. Maybe your internal calculations look at a loan at 4% as high enough to pay off fast, but not one at 2.5%. Makes sense.

However, now most of us can’t deduct that mortgage interest.

Mortgage rates are rising

For the past several years, we have been enjoying historically low interest rates which have translated to historically low mortgage rates. However, that has been changing. A few years back a 30-year mortgage might have been at 3.5% while now it is at 5%.

If you combine that impact with the tax deductibility, you have a major impact. Before you had a low rate that was tax deductible. Let’s say it was a 3.5% rate that “felt” like 2.5% after you deducted the interest on your taxes.

Now if you get a mortgage that rate will be 5%. That’s an enormous change, big enough to fundamentally shift the decision of whether or not you should pay off your mortgage faster.

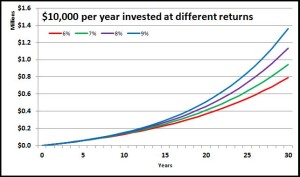

Remember, that paying off a loan is basically making an “risk-free” investment, similar to a bond. Before, paying off your mortgage would give you a 2.5% guaranteed return. That’s not great. For the Fox family, we looked at that as too low. We’d rather take on more risk and invest that money in the stock market.

Now with the changes, being able to get a 5% guaranteed return changes our decision. We wouldn’t do it at 2.5% but we would at 5%. This becomes real because now Foxy Lady and I will start using extra cash we have to pay off our mortgage faster.

This is a huge game changer that impacts millions of Americans. It changed a central decision we had to make for personal finance. Maybe it will change that for you too.