On Monday we asked the insane question: “Is college a waste of money?” We came up with an insane answer: “A person would do much better financially saving that tuition money and not going to college.”

Such a bold conclusion deserves some intense scrutiny. Let’s look at this more closely and see what the key drivers are.

Base case

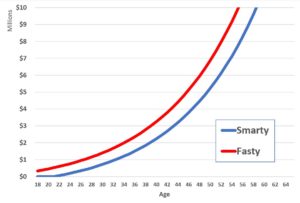

Recall from the last post that Smarty goes to private school ($280,000 total). Fasty works at a job making $36,000 per year straight out of high school and Smarty spends four years in college then makes $60,000 per year once she’s out of school.

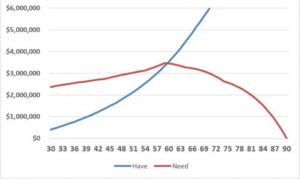

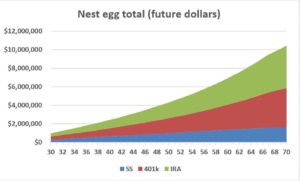

Results—FASTY comes out ahead by $2.7 million (11% better than her sister). This is where we were yesterday. Now let’s start looking at our assumptions.

Scholarships

Of course, this is a big one. Scholarships effectively bring down the cost of college, potentially to zero if you get a full-ride scholarship. The larger scholarship Smarty gets, the more the race tilts in her favor.

Public college

Public college is a much more affordable option, at $100,000 instead of $280,000. Except at the very top (Harvard, Stanford, Chicago) there’s no reason to believe that Smarty couldn’t get as good an education at a public school like University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill compared to an average private school like Wake Forest.

Results—This has a huge impact. SMARTY comes out ahead by $680,000 (4%) if she goes to a public school. It’s not an overwhelming advantage, but the decision between public and private school makes a huge difference.

Wage growth

We assumed that Fasty would make $36,000 her whole career and Smarty would make $60,000 her whole career. Those are the average incomes for people, but in real life people’s wages start lower and grow higher. There’s a lot of debate and controversy here about wage growth and if it goes to everyone or just those at the very top (here is a link that a grad school friend posted).

If you look at more detailed data, it shows that those with college degrees have wage growth 33% higher than those without degrees. To account for this, let’s assume Fasty starts out at $22,000 and Smarty starts out at $33,000. Then let’s assume that Fasty’s wages grow 2.0% each year while Smarty’s grow at 2.7%.

Results—This actually has a pretty low impact. FASTY comes out ahead. If you assume public college Fasty is $233k (2%) ahead which is pretty much a tie. If you assume private college then Fasty is ahead $4.8 million (39%).

College major

Let’s cut to the chase. This is where the real action happens. What you study at college has the biggest impact on what you earn. Starting salaries for STEM (science, technology, engineering, math) majors are 30-50% higher than those for liberal arts and teaching majors.

Also, the income growth is much higher. STEM majors can expect their wages to grow about 50% faster than teaching and liberal arts majors. In fact, teaching majors have wages that grow SLOWER than those people without a college degree. So if Smarty went into teaching, she would make more than Fasty at first, but Fasty’s income would pass Smarty’s eventually.

Results—This actually has a profound impact, even when you assume public college. With a STEM degree, SMARTY will come out $3.0 million (19%) ahead. You can play with the numbers, but it’s really hard to find a realistic set of assumptions where Smarty doesn’t win with a STEM degree, with the possible exception of private college. This is true for medical and business degrees as well, just not to the same degree (degree-degree, did you see what I just did there ??).

As good as things look for a STEM degree they look that dismal for a liberal arts, career-focused (journalism, public policy, recreation, industrial arts, agriculture, etc.), social sciences, or teaching degree. FASTY will easily come out ahead to the tune of $3.2 million (33%) if Smarty gets a liberal arts or teaching degree. This assume public college; if we assumed private college, that would be drastically worse for Smarty.

Master’s degree

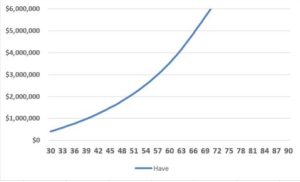

By attending college Smarty will give herself an option that Fasty just won’t have: the ability to get a master’s degree. This is the route I took, going to college and then after working a few years getting my MBA. In a way, this is really more of the same, and links very closely to the “College major” discussion.

Getting a graduate degree doubles down on your college decision. If you pick a major which puts you ahead, typically getting a master’s degree in that same area will puts you further ahead. Conversely, if you pick a major that puts you behind, getting a master’s degree will put you even further behind.

Results—If Smarty gets a STEM degree she’ll come out ahead. If she gets her master’s, instead of being about $3.0 million ahead she’d be about $3.6 million ahead. That’s a bit of upside but not too much. Conversely, if she gets a liberal arts degree and then a master’s on top of that she’d go from being $3.2 million behind to $6.0 million behind. Yikes!!!

Taxes

Taxes always suck, but they are going to hurt Smarty a lot more then they’ll hurt Fasty. Smarty got her degree and got a higher paying job, and that means she’ll be paying a much higher tax rate than Fasty. Fasty makes less money and that helps in two ways. First, she pays a lower tax rate. Second, because her income is low she doesn’t pay taxes on her investment income.

As Smarty makes more money which is really her whole strategy by going to college, that will help her win the race against her twin, but that will also mean she’ll pay higher taxes and that has a moderating effect.

Results—The very best outcome for Smarty was a STEM degree from a public college, and then her master’s. That resulted in her coming out ahead by about $3.6 million. If you add taxes to that, she only comes out ahead about $1 million. That’s still a lot, but taxes are making something that was a total sure thing a bit more suspect.

Of course, if you consider taxes on all the less favorable scenarios for Smarty (private college, liberal arts degree, etc.) it takes a bad situation and makes it even worse.

Smart non-college kids

We’ve been making an assumption that I think is actually flawed, and has the potential to tip the scales in Fasty’s favor pretty drastically. Remember, we assumed that Fasty and Smarty are identical in every way—equally smart and equally hard working.

In our society, smart and hard-working high school graduates typically go to college. That’s just what they do because they’ve been told a million times that is what they should do. It’s a bit of a circular argument.

When we look at the data for high-school graduates with no college, those are people who never went on to college. Maybe they were late bloomers, maybe not ambitious, maybe just plain not smart. Based on my argument above, very few (although some for sure) had the option to go to college and passed it by.

I say all this because what would happen if Fasty is smart enough and hard working enough to go to college but chooses not to? There’s every reason to believe that she would do much better in her career and make much more money that the “average” high school degree person we’ve been talking about.

Imagine she gets an entry-level job at a factory. She is punctual, hard-working, figures out better ways to do things; all those things would have helped her in college but now she is applying that to her non-college job. That will set her apart from many of the other high-school graduates who didn’t have those qualities and abilities, probably one of the main reasons why they didn’t go to college. Eventually her talents will be recognized and she’ll get more opportunities at higher wages. Maybe it won’t be as fast as if she earned her degree, but it doesn’t have to be. Remember, she also has $280,000 in her bank account.

Results—If Fasty’s salary is higher or can grow faster than the average for a high-school grad, then the calculations drastically shift towards Fasty. Remember that Fasty won the race most of the time. It was when Smarty got a STEM degree that things changed, and that’s because Smarty had a higher salary and faster income growth. However, if Fasty’s hard work got her even a little bit higher salary and faster salary growth, she would close the gap.

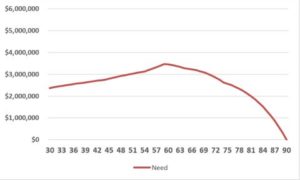

Other considerations

College dropouts—This is the real killer. How many kids start college but don’t finish. They end up with the job prospects of Fasty but without the head start.

Fifth-year seniors—Increasingly college kids aren’t finishing their degree in four years. That is a double whammy because it delays them making money for another year and they have to pay an extra year of tuition.

Living at home—There are a lot of ways to get the benefits of college without the full-blown college experience. Living at home (and eating Mom’s cooking) is one that drastically cuts down the cost of attendance.

We’ve come along way. After Monday’s post I was pretty pessimistic on college. I don’t know if this post made that better or worse.

Definitely we learned that private college makes it near impossible to come out ahead financially. More importantly, what you study makes or breaks the decision; STEM and healthcare and business will probably put you ahead while liberal arts and teaching and social sciences will doom you. There’s other stuff too, but I think those are the two most important.

Come back on Monday when I tell you what Foxy Lady and I are planning on doing with ‘Lil Fox and Mini Fox.