Stocky Fox is thrilled to be joined by his colleague from business school, Tanya Golubeva, who writes the blog about day-to-day life in Russia, www.understandrussia.com.

Stocky Fox: Tanya, thank you so much for chatting with us.

Understand Russia: My pleasure.

SF: Most of my posts are very American-centric, so I know my readers and I appreciate the opportunity to learn how investing works in other parts of the world.

UR: I’m glad to do it. Investing is done very differently in Russia than how you describe it in your blog, so it’s interesting to see those differences.

SF: Obviously I’m obsessed with personal finance, investing, and saving for retirement, but I’m not alone. Saving for retirement is one of the most important issues that people in the US think about. How does that compare to Russia?

UR: It’s very different in Russia. For a bunch of reasons, Russians don’t save a lot. Even the fairly successful ones who are making higher salaries, really aren’t saving much. Certainly nothing like the numbers you talk about in your blog.

SF: Why do you think that is?

UR: One of the main reasons is Russians don’t have a lot of faith in the financial system. It has been so unstable for so long that no one really trusts it. I’ll give you an example with my grandparents. They were frugal and saved for their whole lives. When they retired they had enough to have a comfortable retirement—they could buy several good cars (Volgas were the best), help their kids and grandchildren, all the stuff you talk about in your blog.

SF: That sounds exactly like what we do in the US. So what happened?

UR: In 1991 there was a crazy financial meltdown. Old bank notes were replaced with new bank notes. 50 and 100 Ruble notes issued after 1961 became invalid. People could only exchange their old bank notes during a 3 day window, but no more than 1000 Rubles per person. It was a horrible time and tens of millions lost nearly all their money. So overnight my grandparents lost 90% of their savings. They went from being extremely comfortable to having a very, very modest savings. That all happened literally over the course of a week or so, it was that fast. And that’s just one example.

In my lifetime there’s probably been four or five crises like that which just destroys people’s savings. So Russians just don’t trust that their savings will be worth anything in the future.

SF: That’s crazy. So if people don’t save their money, what do they do with it?

UR: Russians, especially those in the upper class and upper-middle class, just spend a lot of money. We’re always buying gadgets—I’m the only one of my friends who still has an iPhone 5, everyone else has an iPhone 6. People also eat out a lot, and depending where you are that can get really pricy. Moscow and St Peterburg are really expensive cities, and it wouldn’t be unusual to spend $200 per person at a nice restaurant. And we go on vacations a lot because so much of the year it’s dark, and when we go it always tends to be first class. When you are not sure about the security of your savings or investments, it makes sense to use the cash you have here and now.

SF: That sounds like a pretty sweet lifestyle for the wealthier Russians . . .

UR: It’s not just the wealthy Russians. Certainly they have more money to spend than others, but that really applies to all Russians. Any Russian who takes a vacation is going to probably spend more, a lot more, than an average American or European. They’re spending it on nicer hotels, going out to dinner at nicer restaurants—they just want to go first class. “We live once” is the phrase that many people adhere to.

SF: So if Russians are spending so much and not saving, what do they plan to do when they get older and can’t work anymore?

UR: That’s a curious quality of Russians. There is a duality about us in so many things and money is certainly one of them. On one hand we know we need a “rainy day” fund and need to save for that, but we also want to live for today. That’s an internal conflict with most Russians, and typically living for today wins out.

So in answer to your question, no one really thinks about it. When I talk to my friends we discuss all sorts of things—fashion, politics, jobs, relationships—but we never talk about money. It’s a taboo subject. In Russia you can never ask a woman how old she is and you can never ask about money issues.

SF: Shoot. I guess I can’t ask my next question (just kidding). There are very similar taboos in the US. However, it seems that Americans are more open to talking about money if you look at the number of blogs, articles, and television shows about money and investing. So what do people do when they get older?

UR: Most people from my parents’ generation have kids who help them. They may still live together, but more often kids buy their own apartments if they can afford that, but help the parents financially. That said, many elderly are extremely poor (average pension for elderly is about $200 per month), which is very sad. For my generation, getting help from your kids will be a challenge because the birthrate has decreased so much. So definitely something will need to be done, but I don’t think anyone really knows what that will be.

Also, there is a government run pension similar to Social Security, but no one really thinks that’s very reliable. In the past few months, the government has started using funds from that to help finance all the things it is doing in Ukraine and Crimea. I personally don’t think I’ll ever get a kopeck from that. It’s like a lottery, but no one ever wins.

SF: A lot of people say the same thing about Social Security. I don’t know if my generation will get anything from that.

UR: As bad as your Social Security might be, I guarantee you it’s nowhere as bad as the Russian pension system.

SF: But some Russians must save money. What do they do?

UR: First off, there isn’t anything like a 401k in Russia. I know you talk about those in your blog a lot as one of the main ways people save money and invest in stocks. That just doesn’t exist in Russia.

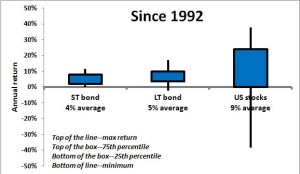

If they do save, the most common way is to deposit money in a commercial bank. Deposits in rubles have high interest rates (in double digits). But the exchange rate went from 34Rub/$ last June to 60 Rub/$ recently, so you ended up losing quite a bit (in terms of dollars) because of that. You can also save money in US dollars and get interest rates between 5-8%, so that’s a really good deal. The government will insure your money up to a certain amount (equivalent to about $20,000), so it’s pretty safe. It’s not uncommon for upper-middle class people to have multiple accounts like this in several different banks.

SF: Holy cow!!! 8% interest on a savings account. That’s what you can get investing in stocks, but you don’t have the ups and downs of the stock market. Can the Fox family give you some money to invest for us?

UR: Sure, just send me the money and I will make sure I invest it in banks that are covered by the State Insurance. No problem, happy to help a friend. In Russia we never “do deals” with friends. I will spend my own time to invest your money and will do all the necessary research and will not charge you any commission or interest rate for that because we are friends. That is how it works here.

SF: In my blog I spend a lot of time talking about how investors should buys stocks (or mutual funds made up of stocks). Do Russians invest in stocks?

UR: Most people do not. Some people do, but these are very few people. First, financial literacy in Russia isn’t anywhere near what it is in the US, even among highly educated Russians. Second, why would we invest in stocks if we can get 8% interest from a bank [Stocky Fox nodding in agreement]? Third, most wouldn’t even know how to invest in stocks. Honestly, I wouldn’t know where to go to open a brokerage account. I would be afraid anywhere I went would probably be a scam, and I’d be right more often than not. So no one really invests in stocks.

SF: You mentioned financial literacy. Why do you think Russians aren’t that financially literate?

UR: You have to understand that culturally stocks just aren’t that visible in Russia. In the US, they’re everywhere; you can’t go anywhere without seeing a company that has a stock that people talk about. I bet for every one Russian company that is publicly traded you have 50 American companies—McDonalds, Microsoft (my former employer), Apple, Coca-Cola. Because of that, Americans probably understand these companies more and therefore understand their stocks. You just don’t have that in Russia. But I think that could be a huge market opportunity.

SF: Market opportunity? What do you mean?

UR: Just look at our conversation. There are many Russians who are educated, making good incomes, and probably know that they need to save for the future (even if they don’t admit it right away). But where would they go to do that? You have places like Vanguard and Fidelity in the US that make it really easy. We don’t have any of those places. Literally, Fidelity and Vanguard are not available in Russia.

If someone started a company that could help Russians understand how saving and investing works (similar to what you do on your blog—the power of compounding), and then allow them to invest with someone who they could trust wouldn’t steal their money, that would probably be hugely popular. I think that a lot of companies tried to do that, but the fact that I cannot name one company I would trust my money makes me think they were not very successful

SF: Hmmmm. I wonder if there could be a Russo-American partnership.

UR: Maybe. I’m telling you, who ever could figure that out would have tons of customers.

SF: On that positive note, I really want to thank you on behalf of all my readers for giving us some insight into how investing and savings works in Russia. It’s definitely a completely different world from what I’m used to here in the US.

UR: I was happy to do it. Thank you for having me. And for all your readers, please visit me at www.understandrussia.com.

SF: I know I will. Thank you, Tanya.

For all my international readers, I plan on doing more of these types of posts that tell us how investing works in different parts of the world. If you would be interested in sharing how it is done in your country, please contact me and we can set something up.