“Ocean waves will grind the greatest boulder into sand if given enough time”

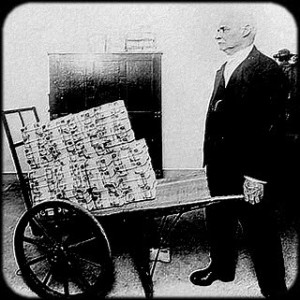

Inflation, the general rise in prices over time, is a powerful and unrelenting force which is eroding the value of your money every year, every month, every day. How powerful is inflation? Look at this simple example with my neighbors, Mr and Mrs Grizzly.

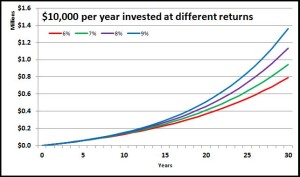

If they want to spend $50,000 per year (in today’s dollars) in retirement they’ll need about $1.2 million on the day they retire (40 year retirement, 6% return, 3% inflation). Every year in retirement they’ll spend a little more than $50,000 to buy what $50,000 buys today because of inflation. However, if you crank the inflation knob up a notch from 3% to 4%, they’ll need $1.5 million. Up to 5%, they’ll need $1.8 million. What makes inflation so scary is that the impact is huge—a 2% increase requires your nest egg to be $600,000 larger—and it’s also completely out of your control.

In the US, inflation is tracked by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, a division of the Department of Labor, with a tool called the Consumer Price Index (CPI). Basically (I know it’s much more complex, but for brevity’s sake) it looks at a general basket of goods that people buy and tracks how those prices change over time. It’s meant to track EVERYTHING that consumers buy: food, housing, cars, airline tickets, medical expenses, entertainment, and on and on and on. The US boasts an amazing record of tame inflation over the decades, but even then it’s been quite a roller coaster: in the early 1980s, according to the CPI, inflation was averaging about 12%, and it has averaged about 1.6% since 2009.

That just ruined Mr Grizzly’s day. So he needs $1.2 million today to retire, but depending on inflation it could range from $1 million to $8 million if it got as high as it did in the early 1980s?!?!?! No bueno. How the heck is he supposed to plan for a range like that?

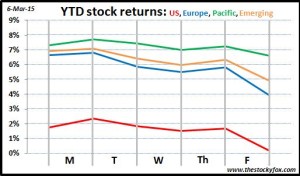

The unfortunate answer is: there really isn’t a good answer. Inflation is going to do what it will do, and there isn’t a lot you can do about it as an investor. The US government sets an inflation target at 2%, but reasonable people can debate how good Washington is at managing stuff like this. When I do my planning for the Fox family, I personally use 3%. But there is some good news—I actually think the CPI waaaaaaay over estimates inflation and that it is going to be on the lower side of historic averages, which is a good thing for those of us saving for retirement (as always, this is just my opinion and may turn out to be quite wrong, also with my projections I am not predicting the future).

The CPI is supposed to compare apples to apples, so basically what did you buy last year and how much would that cost if you bought the exact same stuff this year. I think over the short-term the CPI works pretty well; I’d believe that prices in 2014 were about 2% higher than in 2013 (in line with the CPI’s figures). But over longer periods of time, the CPI really fails because I think it does a really lousy job of dealing with major technological advances. So when you look at 10 or 20 or 50 years, which happens to be the time horizon we’re looking at for retirement, I think the CPI really overestimates inflation.

If you go back to 1965 (I picked 50 years ago, because I figure I have 50 years to live, so that’s my time horizon), the CPI says prices have risen about 7.5 times. So something that cost $100 in 1965 would cost about $750 today. If you do the math, that equates to about 4.1% per year. We saw the impact that the level of inflation has in the above examples (pretty major impact), yet let me tell you why I think the government is getting it wrong and there is some real relief. This is going to be a long post (but I hope a valuable post), so get comfortable.

Cars

In 1965 you could get a new 4-door sedan like the Chevy Impala for about $3000. Today you could get a new 4-door sedan like the Honda Civic for about $20,000. If you do the math, that calculates to about 3.9% inflation per year, right around what the CPI says (I know, you’re saying: “Stocky, so far I’m not impressed.”) But remember, the CPI is supposed to compare apples to apples; when you compare a 1965 Impala to a 2015 Civic, the Civic has a ton of advantages.

The Civic gets 35 miles to the gallon, while the Impala got about 12. The Civic has incredible safety features like airbags, antilock brakes, backup camera, and on and on; the Impala has seat belts across your lap (they didn’t even have the shoulder ones). The Civic has Bluetooth to connect to your MP3 player, while AM/FM was an option on the Impala. A new Civic will probably last you 200,000 miles or more, but your Impala would be lucky to get to 100,000 (like “go-out-and-buy-a-lottery-ticket” lucky).

Put all that together and how much of that 3.9% annual price increase is due to inflation, and how much is due to the Civic just being a better car? It’s not an easy question to answer, but I would think an awful lot of the price increase is because you’re getting a safer, more fuel-efficient, and more durable car . . . just a better car.

To look at it from a different angle, we know $3000 in 1965 would buy you a new Chevy Impala. What would $3000 buy you in 2015? A quick look at Autotrader.com shows that for $3000 you could get a 1998 Honda Civic with 150,000 miles. Between those two choices, each of which is $3000, don’t you have to pick the Civic as the better car? It’s safer, much more fuel efficient, has more convenient features (cruise control, automatic windows), and it will probably last longer. All that says that inflation was actually a lot less than the 4.1% the CPI said or the 3.9% we calculated.

Rent

Housing is the biggest expense that people have, so how does that come into play? In 1965 the average rent was about $90 per month while in 2011 it was around $870 which calculates to about 5.1%. That’s higher than the CPI, but before we freak out about runaway inflation in the housing market, let’s do the apples-to-apples comparison. In 1965 you were getting a place where you might have shared a bathroom with your neighbor and a phone too. You had an icebox instead of a fridge (literally a cabinet that you kept cool with blocks of ice), and radiator heating.

Today you have granite countertops and stainless steel appliances, central air conditioning, and a fitness center downstairs if you’re lucky. How much of that 5.1% increase is due to prices rising, and how much is due to you just getting a much, much nicer place with much better amenities? Today, I’m sure if you tried hard enough you could get a total armpit of an apartment that was completely vintage 1965, and I bet you probably wouldn’t pay more than a few hundred bucks for it, showing that prices for apples-to-apples apartments haven’t risen near that 5.1% level.

Healthcare

Ahhhh. This is where you’re saying: “But what about healthcare? Medical prices are spiraling out of control. That’s where they get you.” The Medical CPI shows that prices have increased an astounding 17 times since 1965—about 5.9% annually. Mr Grizzly just had a minor aneurysm, which he knows is really going to cost him. But before you despair, do the apples-to-apples comparison and realize that the quality of healthcare has gone up exponentially while costs it can be argued have come down.

Let’s say Grandpa Fox had a heart attack in 1965. First, his chances of survival weren’t very good, but let’s assume he survives and gets coronary bypass surgery. After two months of recovery he’s back at home living his normal life, but now with a sweet scar running all the way down his chest from the open-heart surgery. That surgery back then would cost around $6000 (it’s hard to find exact numbers on this so I estimated; any reader who has better data please let me know) which is a drop in the bucket compared to the $100,000 price tag bypass surgery costs today.

Unfortunately, Grandpa Fox passed his lousy heart genes on to me. However, instead of a heart attack hitting me out of the blue, my doctor discovers early on that I have high cholesterol and prescribes me Lipitor which costs about $300 per year, and that is even lower if you go generic. My heart problems get taken care of for much less money, plus I didn’t have to go through a high-risk surgery and brutal recovery.

But maybe Lipitor doesn’t work, so after a while they find my coronary arteries are severely blocked and I get a stent (of course, I only use a Medtronic brand stent). I have a non-invasive surgery where they insert the stent through a tiny incision in my hip, I go home that evening, and it all costs me about $20,000. Like before I probably would have a much better outcome than Grandpa Fox, at about three times the cost which equates to about 2.4% inflation over the 50 years.

So while medical expenses have skyrocketed (and I totally agree they are out of control), if you look at the idea of taking someone with a heart problem and getting them back to health, prices have actually gone way down since 1965. So much for aggressive inflation here; you could actually argue that there has been deflation.

Food

So let’s compare apples to apples, literally. Apples in 1965 cost about 16¢ per pound while today they are about $1 per pound (at least in LA)—that equates to inflation of about 3.6% inflation. But there is actually a difference between 1965 apples and 2015 apples. Back then there was this weird concept of fresh fruits and vegetables being “in season.” You could only buy apples certain times of the year which was around late summer and fall (I had no idea so I actually had to look this up, which kind of proves my point). Today fresh fruits and vegetables are in season when your grocery store is open and you have money. So again, you’re paying more but you’re also getting a better product as well—year round fresh fruits and vegetables.

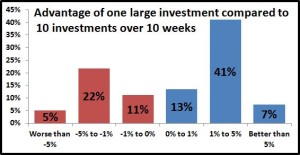

And there are many product categories whose prices have fallen drastically (air travel, anything with electronics), and others that we used to be charged for but are now free (telecommunications, news articles). The whole point of all this is that depending on how you look at it, inflation isn’t going to be nearly as high as the CPI says which is a huge help to savers. That means your dollar will stretch further in retirement than you might otherwise think, and that you’ll need less to retire on. Consider this my gift to you.