Nothing gets stock markets so excited as the Federal Reserve. The United States’ central bank, with a couple well chosen words, can send markets up or down hundreds of points in a matter of minutes. It’s even entered the investing vernacular as “Fed Watching”. Alan Greenspan and Ben Bernanke and Janet Yellen have become household names. But why is the Fed so important? What is it doing that sends the markets into such frenzies?

Basically (and this is very basic, as there is a boatload of nuisance in this) the Federal Reserve, and for that matter the central banks of any country, control the core interest rate. That single, yet enormously powerful tool, allows the fed to influence the economy in a major way.

The guiding mission of the Fed is first and foremost to maintain a healthy level of inflation. In the US that is around 2-3%. Being too low has some problems that reasonable people can debate, but pretty much everyone believes that when inflation gets too high, that’s when really bad things happen. So more than anything, the Fed is tasked with keeping inflation low. Then a secondary goal is to promote a healthy and growing economy that keeps unemployment low. So basically the Fed has two jobs, keep inflation low and keep the economy strong.

How does the Fed impact the economy?

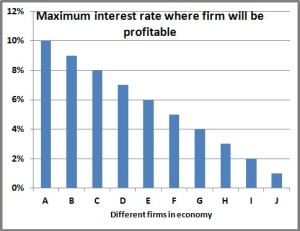

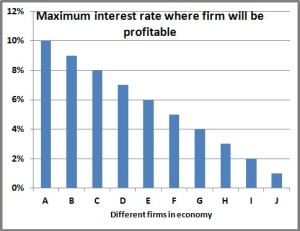

Let’s imagine a really simple economy. There are ten companies named A and B and C all the way down to J. Just like in real-life, not all companies are created equal, with some being much more profitable than others. Here A is the most profitable (maybe like Apple) while J is the least profitable (maybe like JC Penney).

Interest rates will play a big part in the profitability of these firms. As interest rates go up, the amount they spend on interest for all their debt goes up as well. Because A is so profitable, it would only start to lose money if interest rates went really high, up over 10%; however J is much more vulnerable and will become unprofitable if interest rates go over 1%. All the other companies have a similar situation as shown in the graph.

So this is where the Fed comes in. Let’s say the Fed sets the interest rate at 6%. Firms A, B, C, D, and E are all profitable even when the interest rates are that high; but firms F, G, H, I, and J are not. Because of that things won’t look good for firms F-J. Maybe it’ll be so bad that they’ll go bankrupt or maybe they’ll lay off people or put a hiring freeze on.

At 6% interest, you have five firms that are doing well (A-E)—growing, hiring more people, expanding, etc.—and five that aren’t (F-J). And at 6% the economy is performing at a certain level. But what would happen if the Fed lowered the interest rate from 6% down to 5%? One more firm (F) would be profitable, and in general it would benefit all the firms. The profitable ones would be doing even better, and the unprofitable ones wouldn’t be quite so bad off. And that would lead to a strong economy: more “stuff” would be produced and more people would be employed.

So there is very clear relationship that lower interest rates led to a stronger economy. Having a strong economy is one of the Fed’s goals, so that begs the question, “Why doesn’t the Fed push rates all the way down to 0%?”

This is where it starts to get interesting. It’s my favorite topic: Inflation. Remember that the Fed’s first job is to control inflation. Let’s look at the Fed’s decision to move interest rates from 6% to 5%, but now look at it with an eye towards inflation.

In our pretend world, let’s assume at 6% interest rates the economy is doing well. Things are growing and unemployment is fairly low. When interest rates go to 5%, firm F will become profitable so they’ll want to hire some people—makes sense. But remember that unemployment is low, so F is going to need to tempt people who are already working for A or B or C or who ever to come work at F. How does F do that? They pay them more.

F starts to pay people more, but A doesn’t take this lying down, so A starts paying more. This wage increase trickles through the economy. But A and B and even F need to make money, so the increase in compensation they’re paying to their employees gets passed along to consumers in the form of higher prices. When prices start rising, that’s INFLATION. And controlling inflation is the Fed’s #1 goal. So that creates the difficult balance for the Fed—they want the economy to do well but not so well that it triggers inflation.

So there you go. You just completed a course in “Introductory Macroeconomics”.

What’s going on today?

Now that you have that little lesson under your belt, how does that relate to what’s going on with the Fed right now? Currently, the Fed has interest rates at historic lows, at about 0%. Obviously that’s super low, so shouldn’t the Fed be worried about inflation?

Remember the circumstances of how interest rates got that low. At the beginning of 2008 the economy was going strong and the interest rate was at over 5%. But then the financial crisis hit, blowing up the banking industry, and sending the world economy into a very sharp recession. A ton of people lost their jobs (unemployment went up) so prices stayed flat or even started to fall a little bit.

With all this going on, the Fed threw a life raft to the economy in the form of near 0% interest rates. In the intervening years, the economy has rebounded and unemployment has fallen, but inflation has remained pleasantly low. This is kind of the best of both worlds for the Fed—the economy is strong and there’s no inflation. The two things they have to balance are both in happyland, so they have kept interest rates low.

But what keeps them in the news is “the specter of inflation on the horizon.” If you follow this stuff (like I do) in the past few months, every time inflation numbers come out, everyone looks at those and tries to predict what the Fed will do. Earlier in the year when it looked like inflation was picking up, everyone thought and the Fed confirmed that it would probably start to raise rates. However, in recent months, inflation has reversed and stayed low, allowing the Fed to keep rates low. This is the drama that has been playing out for the past 6 months.

Every time this happens the market swings like a pendulum. If rates are going to go up, the stock market gets crushed because firms will be less profitable (as we saw in the lesson above). If that changes and we think rates are going to stay low, the market shoots up like a rocket.

What does it really mean when the Fed changes interest rates?

With all of this, are we just a bunch of idiots? Should we really be so happy if the Fed is keeping rates low, and should we be so bummed if the Fed raises rates?

As the parent of two boys who one day may start sponging off Foxy Lady and me, I think the parent-child relationship is a good analogy.

Imagine you have parents (the Fed) who have a grown child (the US economy). Times are tough for the child (the economy is doing poorly) so the parents help out (the Fed lowers interest rates). The good scenario is that the child starts doing better to the point where he doesn’t need his parents’ help (the economy strengthens so it can withstand higher interest rates). The bad scenario is the child becomes dependent on his parents’ help and is never able to make it on his own.

In this analogy the parents reducing the amount of help they give (the Fed raising rates) is a good thing, isn’t it? It means that the kid is getting things on track and is standing on his two feet. For this reason, I actually think it’s a good thing if the Fed raises interest rates because it means that the economy is strong enough that it doesn’t need insanely low interest rates any more. Yet the markets react in the exact opposite direction.

I get it. Just as the kid would be bummed if the parents said, “hey pal, since you’re starting to make some money now, we won’t be sending those monthly checks”, the companies are bummed that they can’t borrow money so cheaply. But that isn’t sustainable.

I chalk this up to yet another of a million examples of how the stock market acts in a goofy manner in the short term. And another reason why I NEVER try to time the market. I just keep my head down and invest for the long term, regardless of what is going on with interest rates. But watching everyone hang on Janet Yellen’s every last word does make for perverse entertainment.

As the current debate unfolds, what do you think? Is the economy strong enough for the Fed to take away the credit card?