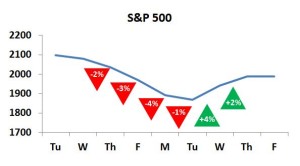

On Tuesday I responded to an email from a worried Mimi Ocelot about the free-fall the stock market is going through right now. I provided a historical perspective of what is going on. In this post I am going to give some reasons I think we’re experiencing all this increased volatility.

And I need to apologize. I started writing this and it got so long (I try to keep my posts at about 1000 words) that I need to split this into a part 2 and a part 3. So enjoy this and then tune in tomorrow for the exciting conclusion.

“The times they are a changin’”—Bob Dylan

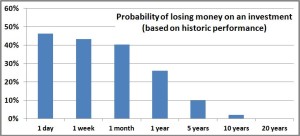

As I wrote here, the volatility in the market is definitely going up. Of those 17 two-week periods as bad as this one since 1950 that I mentioned on Tuesday, eight occurred in the fifty years from 1950 to 2000 which means that nine occurred in the fifteen years from 2000 to 2016. There’s no question that the market has become MUCH more volatile lately. Is this a temporary thing or a new normal? Who knows, but I tend to lean towards “new normal”. Now let’s try to figure out the “why” part of this mystery.

“Ready, Fire, Aim” –Tom Peters (1982)

Nearly everyone agrees that information is the lifeblood of the stock market. Today, that information travels so much faster than in the past. Something could happen in the most remote corner of the world, and you would know about it in everywhere in a matter of seconds or minutes. Obviously quicker access to news is a good thing for society at large, and investing in particular, but it definitely exposes many investors to making big mistakes because they are acting so quickly.

A good example is July 12, 2013. On that day a Boeing 787 caught on fire a Heathrow Airport in London. Here’s some quick historic context: the 787 was Boeing’s next generation aircraft that was going to revolutionize air travel, a plane Boeing pretty much staked its entire future on. In early 2013 two 787s caught fire, leading to the FAA and its counterparts around the world to ground all 787s until Boeing figured out the problem. Boeing’s stock, as you would expect, got hammered. It took Boeing several months, but they fixed the problems, got the 787s in the air again, and their stock recovered.

Then July 12 happened. News broke that another 787 caught on fire. Investors, understandably, concluded that the problems weren’t fixed after all and that the planes would be grounded again. In a matter of minutes the stock cratered, falling from about $108 per share to $99. Over the following hours and days, it became clear the July 12 fire had nothing to do with the previous problems; it was just one of those things that do happen every once in a while. No big deal. Two weeks later, Boeing’s stock was back to the pre-July 12 fire levels. It was all like nothing happened; except it did happen and there was crazy volatility in the stock.

The morale of the story is that investors got the information so quickly and rushed to act on it so quickly, that they completely misevaluated the situation, and that led to a lot of volatility. Had the news traveled more slowly, the world would have had more time for more of the facts to come out. No matter how you slice it, the light-speed fast news makes the pace of investing faster, and when you do something faster, you tend to make more mistakes.

“The chief business of the American people is business” –Calvin Coolidge (1925)

We Americans are probably a bit spoiled. There have been no wars fought on our soil since 1865 (I didn’t count Pearl Harbor, which reasonable people can debate). There has been a consistent government since 1787 (or 1865 depending on how you think about the Civil War) without any coups or revolutions. There’s never been a military takeover of the government, and the US government has never defaulted on its debt. You could go on and on.

The reason that is important is that today about one third of all earnings in the S&P 500 come from outside the US. It’s hard to find out what that number was in 1950 or 1960, but suffice it to say that that number was much, MUCH lower back then. So we have a lot more international exposure now than in the past.

That’s a good thing because of diversification. But it does expose us as investors to some of the geopolitical challenges that I just mentioned, that the US has been blessed to have avoided.

Also, to President Coolidge’s quote, the US tends to be oriented towards business (and some, but not I, would argue too oriented towards business). This has definitely helped us become the largest and strongest economy in the world. But other countries have other orientations (I’ll try not to use too blatant of stereotypes to offend my international readers): the Middle East is very theocratic, Japan focuses on saving face (keeping it from writing off bad debts which has stalled its economy for two decades), China is very authoritarian, Europe is more socialistic. That doesn’t mean any of those other perspectives is bad. But it does mean they are less likely to drive greater business and productivity, and those are not good if your goal is to have your stocks grow.

If you’re exposed to those geopolitical landmines as well as those competing priorities, it shouldn’t be surprising that the road won’t be as smooth. And that’s just French for saying more volatility.

“The world is getting smaller” –Mark Dinning (title of a song from 1960)

Somewhat related to the above issue, the world is getting smaller (don’t think the irony is lost on me that a phrase we use to describe how fast the modern world is changing came from a song two decades before I was born). Everything is so much more connected now, whether it be products (your car is connected to the internet which depends on satellites and under-water fiber optic cable) or countries (the components for your phone probably came from a dozen different countries).

All that interconnectivity is a good thing. It means people/companies/nations can specialize in what they do best, allowing us to get the best products and services at the lowest prices. But that connectivity also means that when the stone falls in the pond in one part of the world, the ripples hit everyone in some way, big or small.

Back in the day when the US economy was largely self-reliant, and even local economies were fairly independent, if crazy stuff happened across the world or even across the country, it didn’t affect things at home that much. That impacts volatility because something is always going crazy somewhere. And of course, that carries over to stocks which react to that craziness. Gone are the days when General Mills was a regional foodstuffs provider for the Midwest; now its stock is affect by the Los Angeles longshoremen striking, the drought in sub-Sarahan Africa, and the revaluation of the Argentine peso. Once again, more volatility.

This seems like a good stopping point. We we’re almost done. Come back tomorrow, same fox time, same fox blog, for the exciting conclusion to “What the hell is going on in the stock market?”