Last week, President Obama released his 2014 financial disclosure. Stocky Fox is going to take the liberty of analyzing the first family’s portfolio, and give my take on what he’s doing right and where he could improve.

First, here’s a quick summary of the numbers:

- $90,000 in checking account. (The disclosure has ridiculously large ranges. For the checking accounts it says it’s between $52,000 and $130,000. In these cases, I just took the midpoint.)

- $3.5 million in treasury notes.

- $375,000 in treasury notes in an IRA.

- $525,000 in Vanguard—the specific funds weren’t specified but let’s assume since their holdings for bonds is so high already, that this money is in stocks.

- $300,000 in 529 accounts for his daughters.

- $75,000 annual pension from state of Illinois when we was a state senator (for 7 years).

- $190,000 annual pension from US for being president.

- Owes $750,000 on mortgage with an interest rate of 5.625%.

The first thing you have to do is put all that in perspective. On one hand it seems like the Obamas have quite a bit. They have assets of about $5 million plus they’ll get almost $300,000 annually in pensions. That’s a lot of money and more than enough to live a very comfortable life.

On the other hand it doesn’t seem like that much. Obama has the most difficult and important job in the world. If you think of him as a CEO of a large organization, his “company” is orders of magnitudes larger than that of any corporate CEO. Yet Obama’s salary ($400,000 per year) and net worth are rounding errors compared to many of those in corporate America.

Also, Obama’s working career has a short shelf life. Once you’re president, you don’t really have a real job after that. John Quincy Adams went on to be a US Representative and Howard Taft went on to be a Supreme Court Justice after their presidential administrations, but that was over 100 years ago. Since then, after your president, you don’t really work. However, there is a ton of potential to make money on the speaking circuit (Bill Clinton made $13 million doing this in 2011). So with all of this, I think the Obamas will be very comfortable in life.

That said, are the Obamas maximizing their investments?

Super high mortgage rate

The first thing is they have a really high mortgage rate. They are paying 5.625%. The going rate for a 30-year mortgage is 4%, so they could easily refinance. Just that alone could save them about $22,000 per year in interest. Maybe that’s not top-of-mind for Obama as he’s leading the US, but I bet one of his aides could do all the paperwork for him. Take about 20 minutes to sign a bunch of documents and he just found an extra 5% of his pay. That’s about $1000 each year for the next 30 year for each minute of work. I wish I had an opportunity like that. Seems like a no-brainer.

Too much in his checking account

Why does he need $90,000 in his checking account? Seriously, what are his expenses? I don’t know how long he’s been parking that much in his checking account, but if we assume that it’s been since at least his second term started, he’s probably missed out on about $50,000 in gains from the stock market. I think he’s sitting on a lot of dead money there.

Good move with the 529s

It’s a smart move saving for his girls’ college with the 529s. I’m guessing that they won’t get scholarships, not because they wouldn’t deserve them, but more because it might seem “inappropriate” for them to accept them. Would the schools be kissing up to the president? Would it create a scandal when it came to light which student didn’t get the scholarship money that went to Malia and Sasha? Either way, if Obama knows he’s going to be paying money for college, at least he’s doing it in a tax advantaged way.

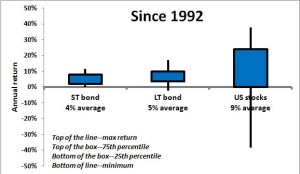

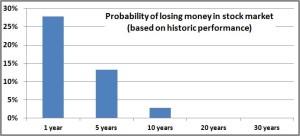

Way too much in bonds

He has about 90% of his assets in government bonds. He’s 53 and Michelle Obama is 51 which is relatively young, all things considered. That would be way too conservative for someone twenty or thirty years older than they, much less two people in their early 50s. And that’s not even counting the value of his pensions. The $300,000 he’s getting each year in pensions would equate to another few million dollars of bonds.

I don’t know what kind of limitations there are on presidential investing (if you do, please let us know in the comments section), but I would assume that he could have a super-broad mutual fund in some type of blind trust that made it impossible for him to favor one company to his own personal benefit. Wouldn’t that be something like the Vanguard Total Stock Index (VTSMX)? Maybe he could diversify to an international mutual fund too and show his counterparts that he’s invested in their economies, literally.

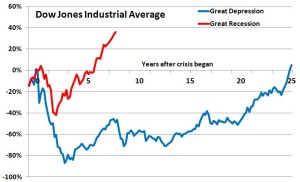

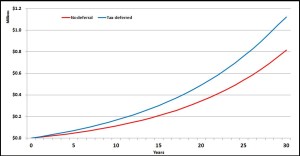

No matter how you slice it, he has left a ton of money on the table by having so much in bonds instead of equities. Just to put it in perspective, stocks have more than doubled since Obama took office. Bonds on the other hand are up about 30%. So maybe instead of being worth about $5 million, he could be worth $10 million.

Of course, this is all a bit of a fool’s errand. The Obamas and their children (and grandchildren) are never going to want for money. If so motivated, he will never have to pay for a meal for the rest of his life. If things do ever get tight, he could pull in a cool $10 million by doing a couple dozen speeches at corporate events. But it’s fun to see how some of the things we discuss on this blog relate to famous people.

In fact, I think it speaks to one of the problems that exist in personal finance today. President Obama is an incredibly smart individual, yet wouldn’t you have to give him a “D” when it comes to what he’s doing with his money? He’s fortunate that he makes a lot of money (and has very bright future prospects), but his choices have left millions on the table. It goes to show that it can happen to the best of us.