I’m trying to build my audience, so if you like this post, please share it on social media using the buttons right above.

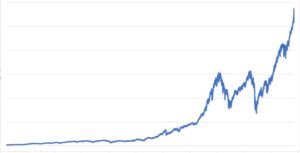

This is probably the most common question you get from people who are considering starting to invest in stocks. It’s pretty understandable; you work hard for your money and the idea of it disappearing into the black hole of an unpredictable and often times not-well-understood stock market is pretty hard to stomach. Add on that scars from the 2008 Great Recession, 2001 Internet Bubble, Black Monday in 1987, Black Tuesday in 1929, and on and on and on. Even recently, 2018 has had a bunch of wild freefalls, including the one we’re in right now.

So, what’s the answer to the question: Who knows? The stock market is unpredictable and no one knows what will happen in the future. That’s not an especially satisfying answer, but it’s the truth. If I could predict the stock market I would own my own island in the Caribbean next to Johnny Depp’s.

But I can hear you saying, “Come on, you’re Stocky Fox. You can do better than that.” You’re right. I’m taking on the challenge and answering the question: Will you lose money with the stock market?

I won’t try to predict what will happen in the future, but I think you can look to how things have behaved in the past, and get a pretty good perspective. Of course, there’s no certainty that the future will be like the past, but that’s the best we have to look at.

You can get somewhat decent data on the stock market going all the way back to 1871. Back then, your great-great-great grandmother was getting The Stocky Fox as a newsletter delivered by the Pony Express. Going that far back, you can calculate the percentage of the time that you would have lost money investing, historically.

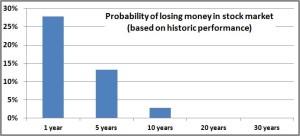

So imagine starting in January 1871 and investing $10 every month in the US stock market. By January 1872, you would have invested a total of $120 and your stocks would be worth $128; congratulations, you just made a profit. You can do that for every 12-month period since 1871 (there are about 1700 such periods), and you come out ahead 71% of the time, which seems pretty good. But the flip side is that you’d have lost money 29% of the time, and at least to me that is too high to be really comfortable.

However, remember that when investing stocks, time is on your side. Do the same exercise but for five years; if you started in January 1871 after 5 years you would have invested a total of $600 which would be worth $679 in January 1876 (yeah, profit again!!!). Do that for every five-year time period and you end up losing money only 13% of the time. By adding another four years to your investing time horizon that decreased the chances that you would have lost money by 20%!!! That seems pretty amazing.

You can keep doing that for longer time periods, and as you could guess, the percentage of times you would have lost money keeps going down. Astoundingly at the 20-year mark, you would have lost money only one time out of the nearly 1500 periods possible (the one month was June 1912 which, you guessed it, was 20 years before the Great Depression bottomed out). At 30 years, there isn’t a single time period where consistent investing would have lost money!!! That’s not a misprint. Read that paragraph again.

There are no guarantees, but if you use history as a guide, it’s pretty much a sure thing that you’ll make money in the stock market. Certainly it involves a lot of discipline, investing month after month no matter how bad things look (dollar cost averaging). Also, it doesn’t necessarily mean you always make a lot of money, but the data seem pretty powerful. Additionally, I didn’t take inflation into account so that would definitely skew the numbers downward (but you know how I feel about the integrity of the data on inflation, so there you go), but the message remains largely unchanged.

I must confess that I was a bit surprised by the data. Actually, I spent about 30 minutes going through the spreadsheet to see if I made any mistakes; I’m pretty confident the analysis is sound. As Dr Brown asked Marty in Back to the Future, “Do you know what this means?” (just don’t take what he says after that and apply it to my analysis). If your time horizon is 20 years or more, at least based on history, there’s virtually no chance that you’ll lose money. I figured it would be a pretty low chance, but zero chance? I didn’t see that coming. Even people who invested for 20 years then pulled out after the Great Recession in 2008 did fairly well (invested $240 which became worth $339).

So there you go. My answer to the question posed at the top is still: No one knows what the future holds. But the historic data confirms my personal belief that the stock market is a really great place to invest your money. I lose no sleep worrying about the Fox family’s investments increasing in value. I know over the long term they will.