We are living in a country where race relations are at a multi-generational low. Despite decades of approaches and policies meant to improve things, up to this point it doesn’t seem to have gotten better (it actually seems to have gotten worse). Maybe personal finance can move the needle? Admittedly, personal finance isn’t going to solve every issue, but I think it is uniquely positioned to make a major impact, all the while without redistributing wealth in a way that makes it a dead-on-arrival policy. Let’s dig in:

Income (and net worth) inequality

Data show that there is a huge difference between the haves (whites, Asians) and the have-nots (hispanics, native Americans, and blacks). Just for simplicity, for the rest of this post we’ll contrast the black/white differences, although this entire post could easily be about black/Asian or hispanic/white or hispanic/Asian and the concepts would be nearly identical.

| Race |

Income (2015) |

Net worth (2013) |

| Asian |

$80,720 |

$112,250 |

| White |

$61,349 |

$132,483 |

| Hispanic |

$46,882 |

$12,458 |

| Native American |

$39,719 |

N/A |

| Black |

$38,555 |

$9,211 |

| TOTAL |

$57,617 |

$80,039 |

The median income for whites is $61k and the median income for blacks is $39k. That’s a big difference, but the difference becomes even more pronounced when you look at net worth–$130k for whites and $9k for blacks.

The income disparity gets A TON more press than the net worth disparity, and that’s a big miss. You don’t eat income or use income to buy a house or pay for college: you use net worth for that. Obviously they are closely related, yet they are different, and the data shows just how uncorrelated they are.

Racial challenges are multi-dimensional, very complex, and nuanced. There’s no single path to address all of them, but I think you get the biggest bang for your buck by closing the income/net worth gap. Obviously, by definition, closing the income gap addresses the income gap (incredible insight there, Stocky) and also goes a long way in addressing the net worth gap.

It also addresses a lot of other racial issues: interactions with law enforcement—police have infinitely fewer negative interactions with rich people than poor people. Education—rich people have much better access to high-quality education at every level than poor people. Healthcare—exact same statement as education. Political voice—exact same statement as education. And on and on.

So the challenge is how to increase the income, and more importantly the net worth, of blacks to get it closer to the levels of whites?

Net positive, not sum-zero

This becomes a delicate subject. An obvious solution is wealth distribution based on race. To address the net worth issues, we as a society could tax white people and give those proceeds to black people. This actually has a name: Reparations.

Michigan congressman John Conyers had introduced a reparations bill in every Congress since 1989. Every single time, the bill never came to a vote and “Died in a previous Congress”. Given it didn’t even have the support to come to a vote it’s hard to imagine having the support to pass both houses of Congress and get the President’s signature, plus withstand the legal challenges. I would certainly be opposed to such legislation.

While people can have a lively debate about reparations in particular, they are extremely unlikely. Broadening that out a bit, I think the idea of punishing/taxing/taking away from one race of people to give to another just isn’t realistic or moral.

That speaks to net worth disparity (give net worth from one race to another), but there is a similar train of thought on income disparity. We could take certain high paying jobs and force companies to employ blacks but not whites. This again causes similar challenges.

Actually, this played out in real life recently at Youtube. Allegedly, they excluded white and Asian men from consideration for some roles. I’m not certain to the legality or illegality of this, but from a PR perspective this is a practice that Youtube (they are owned by Google) vigorously denied. They said they hire “candidates based on their merit, not their identity.” If a private-sector company in an at-will state won’t publicly say they do this, there’s zero chance such a practice would be codified with legislation.

Getting back to the task at hand, that means we can’t address the income and net worth gap by taking from whites and giving to blacks. We have to find a way to increase the income and net worth of blacks that has no impact (or dare I say a positive impact) on whites.

It’s what you do

If you read this blog, you know I am an enormous advocate of personal finance, and “doing the right thing” with your money, whatever that means. We live in a country with very low financial literacy, which means that people don’t really understand concepts of compound interest, appropriate asset allocation, tax avoidance strategies, and much more. That applies to all races.

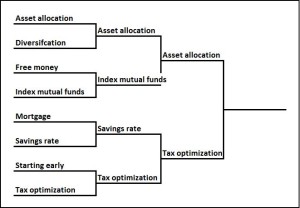

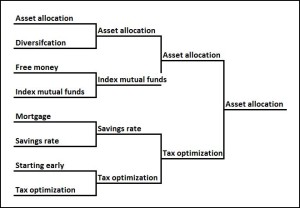

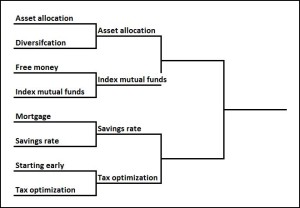

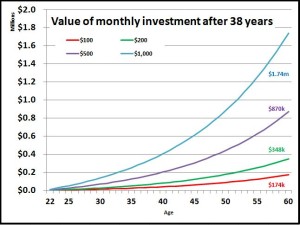

That ignorance comes at a huge cost. Take two twins, Bill and Jill. Bill represents your average American who isn’t too financially savvy, while Jill knows the best ways to invest her money. If they are identical in every way—same job, same salary, same income growth, etc.—Jill will end the game much, much wealthier than Bill.

Just to put numbers to it, let’s assume they each start at 22 with a $50,000 job that grows to $150,000 over time, and they save 10% of their income. At age 60 Bill would have $630,000 and Jill would have $2,640,000. Read that again!!! Jill ends up with a full $2 million more than her twin.

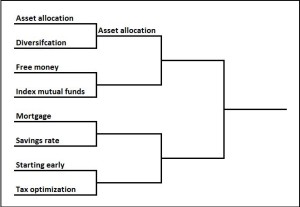

How does such a thing happen? They both made the same incomes, and they both saved the same amount. The short answer is Bill wasn’t smart and Jill was. Bill saved all his money in a brokerage account with a mix of stocks and bonds. Jill saved her money in a 401k (tax avoidance), got the match (free money), and invested in all stocks (asset allocation).

Those are all fairly simple strategies for personal finance, certainly they are ones we have talked about on this blog quite a bit. Those couple gems translate to millions of dollars, literally.

But what does this have to do with race? Unfortunately in our country, personal finance participation is much lower among blacks than whites. That’s short hand for: blacks tend to act more like Bill than Jill. “Personal finance participation” is a tricky term that loosely means having investment accounts, having retirement accounts, investing in stocks, and generally doing what personal finance theory says you should. Make no mistake, it’s an impossible term to define and calculate (which is probably why it’s such a hard problem to tackle).

Certainly you can look at the difference in “personal finance participation” as a function of wealth. Whites are richer than blacks so of course they are going to have more brokerage accounts and 401k’s and all that other stuff. That’s true, but even when you control for jobs and income and the other factors like that, black “personal finance participation” is significantly lower, 35% lower by some estimates.

That impact is ENORMOUS and devastating if your broad societal goal is reducing net worth disparity. If you believe the studies, and use our example of Bill and Jill, the average black person is getting 35% less of the investment gains that Jill got. That’s could easily be a difference of $600k (in reality is probably even more) and that’s HUGE.

GOAL 1—Increase black “personal finance participation”

It’s what you know

Education is a pretty powerful tool, and one that certainly plays a role in the black “personal finance participation” issue as well as the broader income inequality issue.

In college there is a striking disparity between the majors that black students and white students pick. Statistically, black students tend to pick majors which lead to much lower salaries than their white peers. That alone can address the income gap in a major way.

However, we’re going to go deeper into the world of finance. Finance is a pretty good college major, as majors go. I proudly earned my bachelor’s degree in finance from Pitt. The average salary for finance majors is $120k. In a country where the average income for the whole population is $58k, being a finance major seems to be a pretty sweet deal.

Breaking down that by race tells a profound story. About 14% of all college students are black, in line with the total population—that’s a good thing. A similar 14% of all business majors are black—so far so good. However, only 2% of finance majors are black—Houston, we have a problem. Similar to the issue a couple paragraphs above, finance is a high-paying major and black students are picking it way too infrequently.

That leads to two major problems: First, those classes for finance majors are a great way to learn the skills critical to “personal finance participation”. Remember, that accounted to $2 million that Jill had which Bill missed out on. If you take finance courses, you’re much more likely to be a Jill than a Bill.

Second, finance majors get high paying jobs—remember the average salary is about $120k. More to the point of this post, finance majors can become investment advisors (much, much more on this in a second). Data is hard on this, but most estimate that only about 1% of investment advisors are black. As it is, the decisions black college students are making when choosing a major are cutting them off from all of this.

GOAL 2—Black college students major in finance

It’s who you know

Let’s start bringing all this together, shall we?

About 45% of blacks are in the middle class. Add rich blacks to that as well and you’re talking at least 20 million people. That’s a lot.

Based on the “personal finance participation” statistics we know a lot of those people aren’t investing the way they should, and they are missing out on a lot of money because of that. This is true among all races.

I am a financial advisor (I passed my series 65), and my experience tells me that the vast majority of highly-successful professionals, independent of their race, aren’t doing near what they should be doing with their finances. On a scale from 1 to 10, I see a lot of 3s and 4s among people who are incredibly smart and successful.

Fortunately, those people who would be a 3 or 4 on their own can hire someone, and for a small fee bring them up to a 9 or a 10. Jill showed us that being a 9 or a 10 can be worth $2 million (and really it’s a much, much larger number), so if you aren’t there on your own hiring someone to help you seems like a good idea.

Understandably, if you hire a financial advisor, that needs to be an incredibly trusting relationship. Personally, all my clients I knew for at least 5 years before I ever started advising them; also, they’re all white and my age, plus or minus a couple years, and live in my time zone. Once you start working with a client it becomes a very intimate relationship. You learn all sorts of super personal things about your clients—what they spend money on, what are their goals, what do they try to do but fail at, etc. I think it’s even more intimate and personal and trusting than a doctor or a lawyer or a minister/rabbi.

The point of all this is: who are those rich and middle-class blacks going to go to for financial advice? It’s reasonable, and not racist in any way whatsoever, that they would have a preference (possibly unconsciously) for a black financial advisor. Not because of skin color per se, but because of shared experiences and understandings. Someone who grew up how you did, had a similar family dynamic, have similar likes and tastes, prioritizes things in a similar way—those are all really good reasons to pick one advisor over another. Those all correlate strongly with race.

A black person is probably going to have a lot more in common with a black financial advisor. It’s not that you can’t pick someone from a different race for your financial advisor, but there’s an undeniable level of comfort for many. Here’s the rub, at least based on my experience, if you don’t find a financial advisor you’re really comfortable with you don’t often pick the “next best thing,” but rather you don’t use anyone. “Not picking anyone” tends to lead to “not doing anything” and you start to look much more like Bills than Jills.

Let’s be clear, a good financial advisor of any race can help a client of any race. No question. But we live in the real world, and here those personal relationship and trust dynamics are powerful. This isn’t racism, it’s just being comfortable and having a trusting relationship with someone who is dealing with an incredibly personal part of your life.

Clearly the data show this is happening. Blacks participate in personal finance at much lower rates—they’re closer to Bills. And that costs them millions.

GOAL 3—Black financial advisors to work with black clients

Everyone wins, no one loses

Black college students become finance majors and then financial advisors. Because they can relate to middle-class and wealthy blacks better, they get those clients and increase their wealth (becoming Jills instead of Bills).

We wanted to close the income gap. We just found thousands of really high paying investment advisor jobs for blacks.

We wanted to close the net worth gap. We just converted millions of black families from Bills to Jills by connecting them with highly skilled financial advisors.

Clearly, those are two winning cohorts, but there are no losers. As blacks become better investors, that really doesn’t impact the investment returns of whites. The stock market is more like a club with room for everyone, than it is like a high school basketball team where there are only so many spots and if you get a spot that means I don’t. Also, those black financial advisors aren’t taking clients away from white financial advisors; those black clients weren’t using anyone before so it’s all upside.

My local plan

I’ve been trying this with very limited progress so far. I haven’t gotten past step 1, but I’m not giving up.

- Find a couple black college seniors from UNC-Greensboro or North Carolina A&T who are finance majors. Unfortunately, as I mentioned, there aren’t a lot of these and I haven’t had luck so far. But I’m still trying.

- Teach the protégés the ins and outs of investing, not necessarily investment advising but just investing. Actually, it would really just be telling them “read all the posts I’ve done in my blog, understand the concepts inside and out, and then come to me with questions.” We’d work together and get them extremely financially literate.

- Go to a large gathering of rich and middle-class black people (a church, an NAACP meeting, fraternity alumni meeting, whatever) with my protégés . Tell the audience the story of Bill and Jill, and say I’m here to help.

- Work with a couple clients, taking my protégés to every meeting. Legally, the protégés wouldn’t be able to talk or do anything since they aren’t certified, but they could observe and build a non-investment advisor relationship with the client.

- Protégés would graduate, then pass their Series 65 or Series 7, and get a job with some investment company. Completely out of left field ?, the clients I had been working with in the presence of the protégés would leave me for them.

- Protégés would take my clients to their new firms. Given most financial advising jobs are meat grinders where getting new clients is the toughest part, my protégés would have a HUGE head start. That would translate to a higher income, faster promotions, and altogether a better career.

- Rinse and repeat.