I don’t think there’s any doubt that driverless cars are going to change the world. They’ll be safer, cleaner, more efficient, eliminate/reduce traffic jams, and on and on. The future looks bright . . . but what does that have to do with today?

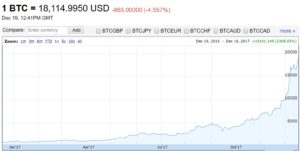

The big question isn’t if but when. A few years back Google and Uber and GM and everyone else were figuring out prototypes, and putting them on the road in a very limited way. They told us not to get too excited—driverless cars wouldn’t become mainstream until way in the future: Think 2030 or 2040 when they became standard fare.

Yet that seems to have inched significantly closer. Tesla today has driveless cars. GM claims it will sell cars without steering wheels and pedals in 2019—THAT’S NEXT YEAR PEOPLE!!!

But back to the question at hand: what does that have to do with today?

Buying a car has big financial implications

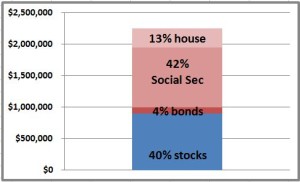

Purchasing a car is a big deal that can greatly impact your personal finances (finally, Stocky, you’re getting to the point). Getting that right or wrong can mean hundreds of thousands or millions of dollars. Let’s really simplify the world to two scenarios:

- The Stocky method: You buy a car new, finance it at the teaser rate, and drive it until it goes to heaven.

- The Ocelot method: You lease a car and then turn it in after 3 years.

Certainly there are other options (1a—you buy a three year old car and drive that into the ground), but let’s just look at these two.

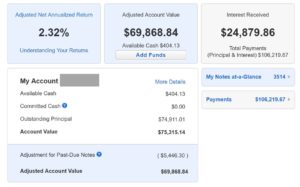

As you would expect, from a financial perspective option #1 wins big time. A “typical” car like a Honda Accord costs about $22,000. You could buy it for $2,500 down and then take advantage of 1% APR financing so you’ll have monthly payments of $332 for the next 5 years. Or you could lease it for $2,500 down, and then pay $200 per month for the next three years; after which you turn the old car in and start it all over again.

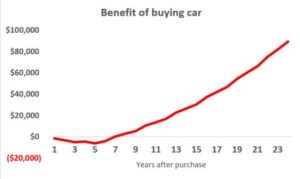

Cars are engineered incredibly well, so let’s assume the car you buy lasts 24 years (I am the proud owner of a 1998 Toyota 4Runner). If you run the numbers, buying a car comes out ahead to the tune of about $90,000. That’s astounding considering the original purchase is only $22,000.

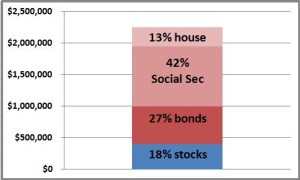

Bear in mind that’s $90,000 per car each time you make a purchase/lease decision. For a married couple, it comes to about $800k over their investing horizon. Remember that the average American has a net worth of about $80,000. Heck, if you didn’t save a dime in your 401k or do any of the other stuff we talk about, just the car purchase decision could fund your retirement.

Of course, it’s not a perfect comparison. The major advantage of a lease is you get a new car every three years—that’s a safer car, a nicer car, plus the option to change the car as your situation changes. But $800,000 is $800,000 after all.

The point is that financially it makes a lot more sense to buy a car than lease.

Driverless cars completely changes the car purchasing decision

Let’s bring this full circle now. We’re on the brink of driverless cars changing everything. Once they come out, you’d be crazy not to go with that option. In fact, I think car insurance will make it much more expensive not to use driverless cars, and before too long human-driven cars will be banned (the same way horse carriages are banned on highways today).

We’re definitely in the kill zone. Foxy and I are wondering how much longer the 4Runner has—I say many more years but I think she secretly tries to put sugar in the gas tank to kill it when I’m not paying attention.

If we had to get a new car today, what would we do? Normally it’s a no-brainer: you buy a new car and drive it forever. However, for that decision to make sense you have to drive that car for years. Actually, the breakeven point is at about 8 years. Is there any doubt that by 2026 we’ll have really good driverless cars? At the rate things are going, we’ll have them in 8 months, not 8 years.

Futurists make a really exciting debate about what the future of cars will look like. Personally, I think ‘Lil Fox and Mini Fox will never own cars. Rather they’ll subscribe to a service similar to your cell phone: for $300 per month you get your 16-mile work commute (with up to 2 other commuters, 2 minute max wait time) plus 500 miles of other driving in a 4-person sedan (with up to 100 miles in a minivan or SUV).

That will fundamentally change things like car insurance, garages (both at home and parking structures), and a million other things. And I bet it’s a lot sooner than we think. Bear in mind, 5 years ago, everyone was saying driverless care are decades away; now GM says it’s a year.

In the meantime, we have to still get to work and pick up groceries and take the kids to baseball practice today. How does all this impact what you want to be a sound financial decision if we have to get a new car today?

The verdict—lease your next car

While this pains me to say, I think the best financial move for your next car is to lease. Who would have thought I would ever type those words?

If you buy, in 10 years or so you’ll be just getting ahead on your financial decision, but you’ll be sooooo behind the times plus be a bit of a hazard on the road. Imagine hanging out with your friends as they take selfies and you pull out your Blackberry.