Over the past few years the Fox family has become big fans of Craigslist. For those who don’t know, basically it’s like a classified section on line. You can sell stuff you want to get rid of, or you can buy stuff that you would be okay purchasing used.

Thanks to this crazy invention called the internet, which seems to be at the root of many inflation killers, you can buy and sell used things with an experience about a million times better than just a few years ago, when everything was done with the classified section of your local news paper.

Craigslist allows you to describe your stuff in as much detail as you want. Newspapers limited you to maybe 50 characters; on the internet you could write 50 sentences if you wanted. Also, with Craigslist you could include as many pictures as you want; no such luck with a newspaper. Plus, Craigslist has features that allow you to filter the results to get exactly what you want and see where you would pick up the stuff on an interactive map. That’s a long of way of saying it’s so much better than the newspaper classifieds.

But who really cares about buying used stuff and how the classified section has entered the 21st century? Well, a lot of people. I don’t have exact figures, but Craigslist it’s one of the most heavily viewed sites on the internet, and because of it (again, no hard figures) it has substantially increased the “second-hand” economy.

If you’re a seller

If you’re interested in selling your stuff on Craigslist, the obvious advantage is that you’re taking stuff you don’t really use any more and you’re selling it for money (that’s pretty obvious, Stocky). Maybe before Craigslist, you’d PAY the newspaper to list your stuff in their classified section, including all the time and effort that entailed. A rather small audience would see the ad, plus there are all the limitations I mentioned before, and you might be able to sell it. Or more likely, you’d avoid all that hassle and either throw it away or give it to the Goodwill.

Now there is a real market for the stuff you don’t want anymore. You can pay $300 for that dresser, and after a few years, when you move or your tastes change, you can sell it. My experience is that most things sell for about 50% off the cost of the product new. So instead of that dresser costing you $300, it costs you about $150.

The Fox’s have sold a couple sofas and other odd bits of furniture, plus we sold a ton of stuff when we moved from California to North Carolina. Maybe total over the past five years it’s added up to $500. So that’s definitely not going to change our finances but it’s better than a stick in the eye.

If you’re a buyer

The obvious advantage of buying used products is you get them at a substantial discount. Sure, it’s a little less convenient because you have to look around for what you want instead of going to a store knowing they’ll have it in stock, but decide how much that’s worth to you. Plus, there is a whole class of people who enjoy searching for the stuff they want on Craigslist. It’s like a Where’s Waldo for baby furniture.

Also, when you buy something used, it probably isn’t as good as if you bought it new, but that varies considerably with the type of product. I would never buy anything electronic (computers, televisions, phones, etc.) used. But I have no issue buying clothes, furniture, tools, toys, exercise equipment, and other stuff like that used. For those, I can pretty easily and quickly evaluate if it’s any good or not just by looking at it. And I find, similar to my feelings on generic products, the more I buy from Craigslist and have a good experience, the more different types of products I’m willing to buy.

This is where the Fox family has been much more active. We bought our baby furniture, at least two futons, a refrigerator for Mimi Ocelot, lawn chairs, a 22-foot ladder, a mini basketball set for ‘Lil Fox, a fair number of tools, my bike and the kid trailer, my bowflex weight set, my little sailboat, and probably other things I can’t even remember now. Let’s say that’s $8000 of stuff if we bought it new, and we probably paid less than $2000 for all of that. Now we’re starting to talk about some serious money.

Double the pleasure, double the fun

You can even buy and then sell stuff on Craigslist, which substantially lowers your costs, possibly even making your ownership of the product profitable. This is kind of like renting with the option to buy. You buy something, and then when you’re done using it or you don’t need it any more, you can get your money back.

Of course you aren’t guaranteed to get all your money back, but sometimes you can. When I was single I bought a dining room set for about $250. Foxy Lady hated it so when we got married I sold it for about $300. I got the use of a dining room set for a couple years before profiting $50. Not bad. We’ll probably do the same thing with the baby furniture. We bought it for $400, had two boys grow up using it, and in a year, when Mini Fox is ready for a big boy bed, we’ll sell it for $400 or $500. Not a bad deal.

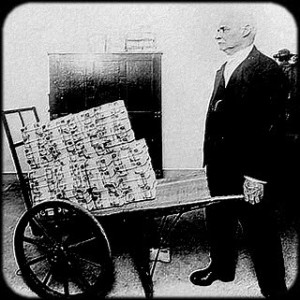

The whole point of all this is that in a real way the costs of stuff you buy is going down. That’s DEFLATION, not inflation. Of course, there is a little more work that goes into using something like Craigslist, but I have found it isn’t very much. But with this, the stuff you buy new is more valuable because it will have a higher resale value when you do decide to sell it. And the stuff you buy used you are getting at a substantial discount. If you buy and sell used, you’re costs go down even more. Add all that up and it just goes to show that there are ways around inflation and keeping your prices down.

Environmental impact

So for in the column I focused on the costs of the stuff you’re buying and selling, and that makes sense because this column is about inflation and personal finance. But there is also another major advantage of buying off Craigslist: the environment.

When you buy something used, you taking something that otherwise probably would have ended up in a landfill. Similarly, when you buy used, some company isn’t mining for iron and copper or chopping down trees or turning oil into plastic. I think about my Bowflex weight machine. Just the mass alone, probably 200 pounds of plastic, rubber, and steel; all means that all those raw materials can stay in the ground. I don’t know if that is important to you. It’s important to me. The fact that I can save money and do something good for the environment makes this a double bonus.

Either way, it shows that inflation isn’t near the specter that people make it out to be. What about you? What have been some of your finds on Craigslist?