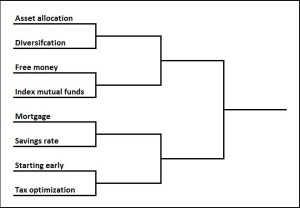

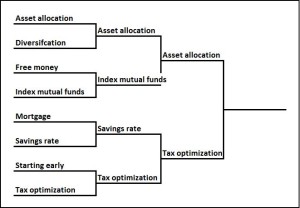

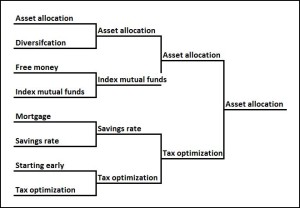

This is what we’ve all been waiting for. After two weeks of amazing investing tournament challenge action (just indulge me, will you?), in this post we will crown the champion of investing strategies. Here we have Asset allocation taking on Tax optimization. In the Final Four, Asset allocation pounded Index mutual funds with higher returns early on and limiting risk as you approach retirement. Tax optimization made it two thrillers in a row, beating Savings rate on the strength of major tax savings with a little bit of work and education, but not a lot of monetary sacrifice. As always, see the disclaimer.

Obviously both these strategies have tremendous upside, otherwise they wouldn’t be here. So how do you pick between them? It’s no easy task, but for you, my loyal readers, I’m ready to take it on. Let’s see who cuts down the nets.

Reasons for picking Asset allocation:

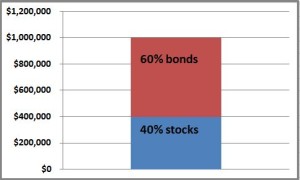

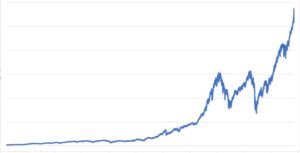

In some ways Asset allocation seems really easy, since all you’re doing is figuring out what percentage of your portfolio goes into stocks, bonds, and cash. 90% Stocks, 10% bonds, and 0% cash; there, I’m done. That didn’t seem so hard. Obviously it’s more complicated than that. We already know that Asset allocation is critically important throughout your investing time horizon. When you’re younger you probably want to be mostly in stocks (even now the Fox family is 99% in stocks). As you approach and ultimately enter retirement you want to be more in bonds, but stocks still probably need to be a significant part of your portfolio.

About 10 or so years ago, the mutual fund companies came out with a really cool innovation called target-date funds. The basic idea is that these handle your Asset allocation for you. Imagine today you’re 35 and you want to retire when you’re 60, in 2040. You could invest in a fund like Vanguard’s Target Retirement 2040, and it will automatically shift your Asset allocation from mostly stocks today (currently it’s about 90% stocks, 10% bonds) to gradually less stocks and more bonds as you get closer to retirement. It’s been a wonderful innovation that has proven extremely popular among investors.

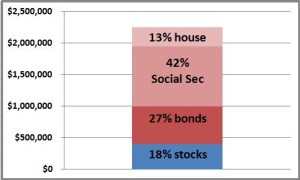

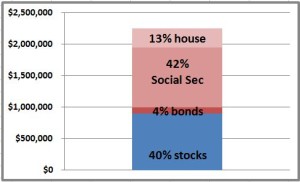

So there you go. Problem solved, right? Well, not so fast. I actually don’t think these really solve the Asset allocation problem because they figure everyone retiring in 2040 is in the same situation, but that’s definitely not the case. Let’s say you and your twin retire in 2040, but you will get $1000 from Social Security while she’ll get $3000. What if she had her house paid off completely while you have always rented? What if you worked for a company with a 401k and she worked for a company with a pension?

All those scenarios are very real for investors, and require more individualization than knowing you want to retire in 2040 can give. For all those, conventional wisdom would say that your twin should take on more risk (French for “invest in more stocks”) than you because she has other “assets” that are generating more cash. Reasonable people can debate that last point, but clearly the idea is that Asset allocation is much more complex than just picking a year and being done with it.

So where does that leave us? I am a firm believer in investing DIY, and Asset allocation is no different. But I think this is one of the areas where the degree of difficulty is much higher just because you’re balancing a couple opposing forces and there’s never a clearly “right answer”. You want to be in stocks but not too much in stocks, and then that changes over time. Oh yeah, and the stakes are super-high. Getting it “right” whatever that means could give you an extra few percentage points in return and it could also save your nestegg from catastrophic failure if another 2008 rolls around. When I work on the Fox’s nestegg, this is probably where I spend the most time.

Reasons for picking Tax optimization:

As we’ve said ad nauseam, Tax optimization is important and can lead to enormous savings. What makes taxes so difficult is that the tax code is constantly changing and the stakes are super-duper high (the stakes for Asset allocation were only “super high”).

Every year there are hundreds of changes to the tax code which keeps accountants employed and programs like Turbo Tax (the Fox family uses Turbo Tax) flying off the shelves. With the new tax reform bill that just passed, there were major changes to your taxes like the deductibility of mortgage interest and local taxes. Those changes have massive implications on choices of where to live–both at the level of which state to live in but also whether to buy or rent. These were huge and made the news. What about the others that do hit the media’s radar and you never hear about?

There’s always talk about more changes, perhaps profound ones like a wealth tax. You have to keep up. Also, it can get really confusing. I think I’m fairly knowledgeable on these matters but I am still befuddled by the Alternative Minimum Tax, and I know I screw up the foreign interest paid on my international mutual funds. This stuff definitely isn’t easy.

Also, look at the stakes. If you screw up on your taxes, theoretically you could go to prison. If it’s an honest mistake I don’t think the Internal Revenue Service will push it that far, but horizontal stripes are definitely in play as Wesley Snipes can attest. What is more likely is the IRS will hit you with a fine composed of a penalty plus interest. Oh, by the way, that interest rate is about 6%; that’s not “Pay-day Loan” high, but it’s still pretty freaking high these days. That certainly can make someone cautious about how far to push Tax optimization, even when they’re clearly in the right.

However, there is a silver lining. If you want professional help, there are thousands of Certified Public Accountants who are there to help you out. For under a few hundred dollars most people can probably have their taxes done by a CPA who can make sure that you stay on the IRS’s good side. Unfortunately, when it comes to developing creative Tax optimization strategies, my experience says there’s a huge range in quality that you’ll get from CPAs. Several years back I had a horrible experience with H&R Block and thought they were border-line incompetent. No way would I trust them to advise me on the finer points of maximizing the tax advantages of investing. But there are amazing CPAs out there right now (like David Silkman who did our small business’s taxes when we lived in California) who I do think can really help. But this is a real caveat emptor situation. Maybe Angie’s List might help.

Who wins it all?

It all comes down to this. In the end, I have Asset allocation pulling it out 76-70. Obviously both investing strategies are amazingly important and getting them right can have an exponential impact on your portfolio. For me I gave the nod to Asset allocation over Tax optimization for a couple of reasons:

First, if I met a total train wreck of an investor (he was just stuffing cash in his mattress) and I could only give him one piece of advice, I think it would be to get that money invested in some combination of stocks and bonds. Tax optimization strategies like an IRA or 401k are nice, but first things first.

Second, I think the big rocks for Tax optimization seem to me better understood and more accessible than for Asset allocation. Most investors probably know that investing in your 401k or an IRA is a good idea, and probably most could tell you why (at least be able to say “it helps with taxes”). I think that’s different for Asset allocation where you have a lot of investors who are totally off on what is probably appropriate for their situation (age, income, other assets, etc.).

Third, there’s no real “right” answer for Asset allocation. I could have a lively debate with my dear friends/loyal readers who work in the financial industry like Jessamyn and Mike, where we argued whether the Fox family should be more in stocks or more in bonds. But there’s no right answer (other than if stocks go up a year from now, then you know you should have been more in stocks). It depends on so many variables as well as risk tolerance which are super-hard to quantify. With Tax optimization you can get closer to a right answer—either the tax code allows you to do that or not. Of course, you typically sacrifice ease of access to your money for tax benefits, so that does add a complication.

Finally, I think it’s easier and cheaper to get expert advice on Tax optimization. As I mentioned, a good CPA can probably really help guide you on Tax optimization. Sure, the quality of CPAs is pretty wide, but good ones are out there, and probably they’ll charge you something with in the three-digit range. With Asset allocation if you want professional help you typically need a financial adviser. Unfortunately, and this is just my opinion, it’s a little more Wild West for financial advisers than CPAs. A really good financial adviser is probably worth her weight in gold (140 pound of gold is worth about $2.6 million, so maybe they aren’t worth quite that much), but the range of quality is staggering; there are some real shysters out there. Also, they’ll probably charge you in the four- or five-digits range.

So there you go. Put that all together and I think Asset allocation comes out on top 78-71, finishing the sentence, “if you only do one thing in investing make sure you get Asset allocation right.”

I hope you have enjoyed reading all these posts on investing as much as I have enjoyed writing them. While Asset allocation “won” remember that all eight of these are important and should be definitely be considered as you think about bulking up your portfolio.