The normally very calm and thoughtful T. Lee (a good friend from my Medtronic days) expressed some strong anti-Trump feelings in a comment a couple days ago. That puts him in good company with a large portion of the country. But then he asked the following question:

“At what point, if there is one, should we consider pulling our money out of stocks and investments and holding cash, based on the disorder, confusion, and unbelievable uncertainty this tiny man of a president is causing domestically and abroad? Are there any telltale signals? I also ask because the housing market and stock market are at historic highs, and seem due for a pullback. I know it’s impossible to time the market this way, but just wondering perhaps there is an exception under extraordinary times.”

Let’s dig into this and see what we come up with.

Things aren’t that bad

Times are insanely partisan right now. If you don’t like Trump it’s easy to think we are on the brink of oblivion, but things aren’t really that bad. Let’s look at some times when things were REALLY bad and how stocks did (some of this is from a post I did a couple years ago so you can check that out here).

Let’s think of the worse times in the past 100 years. A short list probably includes the start of WWII, the atomic bomb dropped, and the assassination of MLK. In each of those things look bad, really bad, and maybe we would have thought that things were about to fall apart:

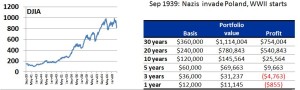

When Hitler invaded Poland and started World War II (Sep 1939)

When the US dropped two atomic bombs on Japan and started the nuclear era (August 1945)

When Martin Luther King was assassinated setting of some of the worst race relations since the Civil War (April 1968)

The civil unrest that’s going on in the US right now is a drop in the bucket compared those examples. Even so, when things looked darkest, being an investor turned out to be a good thing. That table looks at if you invested $1,000 per month starting at that bad event in the Dow Jones index, and how you would have ended up over different time periods. Over a 20- or 30-year time horizon we know that we almost always come out ahead. That definitely held true even in these examples.

I don’t think we have anything to worry about as investors because of Trump or all the current drama. It’s important to keep things in perspective.

Pullbacks do happen

Definitely there will be a point when stocks will pull back. That’s just the nature of the stock market. Given that Trump has taken so much credit for the rise in the stock market, it will be interesting to see how he tries to avoid blame when it has a bad few months or a bad year. Of course, he has shown his ability to grab credit and shed blame as well as any politician, so I’m sure he’ll come up with something.

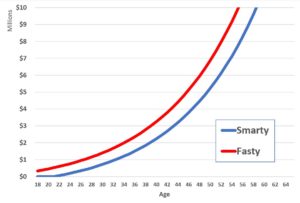

In my post where I proved I was smarter than a Nobel Prize winner, I based that on the fact that two years ago Robert Schiller predicted stocks would not do well. I disagreed and was much more optimistic. Since then stock have been on a major tear, so there you go.

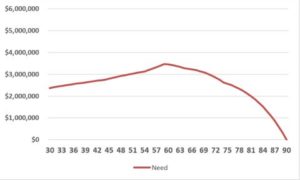

But it can’t last forever. Here are the stock returns for each of the last nine years since the Great Recession: 28%, 17%, 8%, 9%, 29%, 9%, 0%, 13%, and 12% so far this year. That’s a dream, and eventually we’ll take a pause from that incredible pace, but of course we don’t know when that will happen. Robert Schiller, one of the very smartest people in the world, predicted it a couple years ago. Maybe it will be this year (I did suggest maybe we’re seeing some early signs), or maybe it will be two years from now. If it’s two years from now, there could very well be another 10% or 20% upside that you don’t want to miss. As always I recommend holding tight and doing the long-and-steady investment strategy.

Bubbles

Despite the craziness going on in the White House right now, things actually seem fairly strong in the economy which makes me think a huge bubble burst unlikely. If you look back over the past major financial bubbles in the US three come to mind—the Great Depression (1929), the Dot com bust (2001), and the Great Recession (2008)—the issues that caused those don’t seem to be in place.

Of course, it’s impossible to predict what will cause a bubble but if we look at those in turn I think we’ll see that things look okay.

Great Depression—That was the big one that was caused by a perfect storm of bad stuff. You had an insane asset bubble that captivated the nation and was held up by fraudulent companies. It was so bad that most of the SEC laws came about afterwards. What is going on now isn’t anywhere close to that.

Dot com bust—Again we had an asset bubble where stocks that had no profits, and no prospect of getting profits any time soon were being valued through the roof. Maybe there’s a bit of that now, but it seems fairly tame compared to back then. Now companies like Amazon and Apple dominate the news, but those are very profitable companies.

Great Recession—This actually had little to do with the stock markets but more to do with the big bets banks were making backed up by small amounts of equity. Things went bad for a bit, but then rebounded quickly.

That’s a quick rundown, and there’s a lot of detail we could go into for each of those, but none of those telltale signs seems to be with us now. Banks are stronger than they were, there doesn’t seem to be widespread fraud, and the stocks driving the market are profitable. But bubbles by their nature are hard to predict, so who knows.

That said, I will give you the steady advice that I always do which is to sit tight, do dollar cost averaging, and in the end you will very likely come out ahead.