I’m trying to build my audience, so if you like this post, please share it on social media using the buttons right above.

After you do all the smart things with investing and become rich, you then have to show others how you’re better than they are. Afterall, what’s the point of amassing wealth if you can’t feel good at the expense of others.

Early in my life (the 1980s and 1990s) this was easy. You could buy expensive stuff, conspicuously display it, and you were set. Life was easier back then—the more expensive something was, the better it was, and the better it made you.

However, in my adult lifetime (let’s say starting in the 2000s), it seems that centuries-old, tried-and-true concept has been thrown on its head. Those outward appearances of wealth, namely expensive things, have become less reflective of your wealth (or what you would like others to think your wealth is). Some of it is technological advances, some of it societal changes, some of it changes in taste. But it’s undeniable that it has become cheaper to be rich.

Watches

Growing up, a Rolex was wealth and success in its purest form. As far as watches go, they are beautiful but not the greatest timekeepers. A mechanical watch can’t keep time near as well as a quartz or digital watch.

Yet, when I was a kid, if you saw someone wearing a Rolex and another person wearing a Timex, it was clear which one was, or at least seemed, richer and more successful. Of course, that wasn’t necessarily the case (see, The Millionaire Next Door).

For me personally, my parents gave me a Rolex as a gift when I graduated from Pitt. They were giving me a watch but so much more. It was a sign of my accomplishment, my achievements to that point, and their confidence of my future successes. Congratulations to Rolex’s marketing department.

Today I still have that Rolex but I never wear it. Rather, I wear a smartwatch. Despite being rich, I choose to “show off” my $150 Apple watch instead of my $6,000 Rolex. Certainly for me it has a lot to do with functionality: my Rolex tells me the time and date (and those not very well), while my smartwatch tells me those plus emails, texts, my calendar, a stopwatch, the weather, and on and on.

People can always choose function over fashion, but I think even with fashion the smartwatches have eclipsed the expensive timepieces. If you got 100 millionaires in a room, do you think you’d see more smartwatches or Rolexes? I think smartwatches in a landslide.

The point is, if you’re rich, you don’t need to have a four-figure watch on your wrist. You’d more than fit in at a small fraction of that.

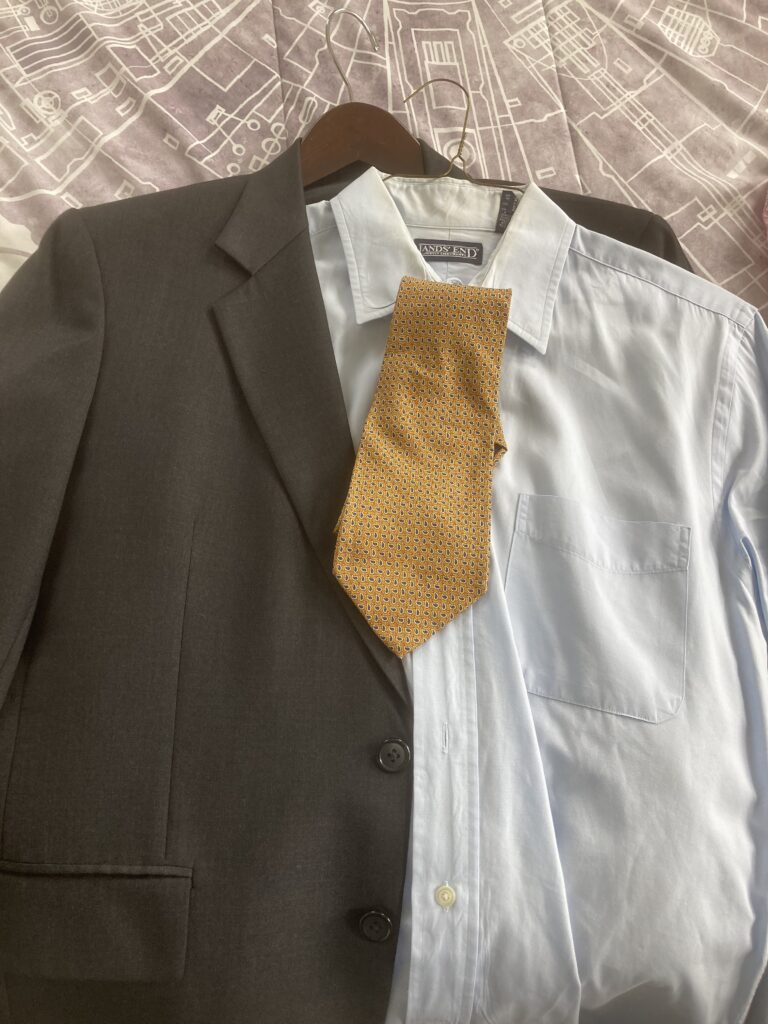

Clothes

Clothes have always been a fashion item, and that continues to this day. It boggles my mind that some jeans can cost $20 and what looks to my uneducated eye as the exact same thing can cost $300. Whatever.

That said, a couple decades ago it was a lot more expensive to dress like a successful person, especially at work. My professional career started with Medtronic at the very end of the 1990s. That was just when corporate America was transitioning from suits to business casual.

Of course, if you were rich, that meant you had a good job, and if you had a good job you had to dress the part. A typical work outfit would be a suit ($300—and these are moderate prices, you would certainly go much, much higher), a dress shirt ($30 plus dry cleaning), and tie ($20). Compare that to a business casual outfit of the same caliber which would be a button-up shirt ($30) and chino pants ($30).

That’s a difference of $350 compared to $60. And that doesn’t account for the little extras on a suit that could accentuate how rich you are like cuff links or a tie clip. Plus, it’s even more expensive in that back then you needed both the suit and the casual clothes. So your total cost was $410.

Today you don’t really need the suit at all and can just get by with the business casual. You’d look just as rich as before but just have to spend a lot less money.

Cars

Cars are another way to really show off how rich you are. There have always been cars to get you from A to B. But it seems there’s been a real change in how we perceive them.

As a kid, I remember that Mercedes or BMWs represented the cars that rich people drove. Sure, there were Yugos and Civics and Chevettes that did the same thing, but they clearly weren’t driven by rich people.

That price difference, back then a top of the line was $80,000 and a lower-end car was maybe $9,000, made a huge difference in perception. I am sure it happened, but I couldn’t imagine a millionaire choosing a car like the one we had (haha!!!) over a Mercedes with every bell and whistle imaginable.

Today, I think brands like Prius and Tesla have turned that logic upside down. A top-of-the-line Mercedes or BMW costs about $130,000 and a Ferrari or Lamborghini is in the $250,000. Compare that to a Prius at $25,000 or a Tesla at $40,000.

At least for me, if I saw a Prius lined up next to a Mercedes S-class, I wouldn’t necessarily think the Mercedes owner was richer than the Prius owner, rather I would think they were different. One was more ecologically conscious, and that could very well correlate with wealth. Back when Foxy Lady and I lived in LA (in the early 2010s) Priuses really took of and I felt at the time they were every bit as fashionable as a BMW 7-series, maybe even more so.

The point of all this is that as society has evolved over the past 20ish years, fashions for the rich have changed. They have changed in a way that makes those really expensive outward appearances of wealth less important and less closely linked to how rich you actually are.

To me that’s a great thing. I’m a millionaire but I am also EXTEMELY cheap (cut to Foxy nodding in agreement). It’s looks like I’ve finally become fashionable.