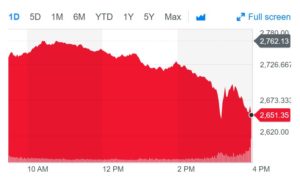

Yowza. Yesterday was a crazy day. There’s an ancient Chinese saying: “you are lucky to live in interesting times.” Definitely the past couple days the stock market has been interesting.

Yesterday I got cocky and wrote a post on the 666 point fall on Friday. I was a bit aloof, and the investing gods love nothing more than to humble people like that. So in a weird way, I take some of the responsibility for the 1175 point drop yesterday.

Seriously though, let’s take a look at what’s going on. Here are my Top 5 impressions of what happened, and what it all means.

- Biggest point drop in a day

Yesterday’s 1175 point drop for the Dow was the largest of all time. Living in interesting times, right? But at a 4.1% decrease (I’m going to be using S&P 500 for percentages just because it’s a broader market and the data is easier to get), yesterday was about the 30th biggest drop since 1950.

A top 30 (or bottom 30 depending on how you want to look at it) is notable given there have been over 17,000 trading days since 1950. However, top 30 means that on average, something like this happens about every other year or so. Maybe not so special.

Remember the last time we had a drop this big? Of course you don’t. In August of 2011 there was a -4.5%. Actually, August 2011 was a crazy month—there were FOUR days with percentage drops greater than the one we had yesterday. Think about that for a second. The month of August 2011 was a major rollercoaster with a lot of ups and downs. Stocks were down 5.7% for the month. But we don’t remember that at all because it was just a blip. Just. A. Blip.

That’s how I think we’ll remember this one. There are never guarantees, but this stuff happens all the time in investing during your 60+ year investing career. Get used to it.

- See the horrors of automated trading

Look closely at the daily chart right around 3pm. It took a super-steep nosedive, at that point falling to about 1500 points. But then, nearly as quickly it recovered about 500 points. That a huge swing in about 10 minutes.

What caused that: Automated trading. Computers saw all the selling around them and were programmed to sell too. However, what should be very comforting is that humans (and other computers with different programming) saw that and realized that the selling was overdone. They stepped in and started buying.

Computer algorithms are a newer phenomenon in the market. I did a post of how they lead to much more volatility (written the last time the market went really crazy). However, while volatility may rise, it really doesn’t have any long-term impact on returns.

But the lesson here is realizing that a lot of what goes on is driven by thoughtless, emotionless computers that don’t really realize if there is an “overreaction”. As a human who has perspective, that means you can keep your cool when that stupid machine thinks it’s all going to hell.

- How bad are things really?

This is important. What has fundamentally changed since a week ago when stocks were at an all-time high?

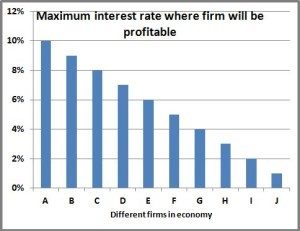

Really not much. There was a jobs report that showed wages had crept up a bit. On top of that Janet Yellen has stepped down as Chairwoman of the Federal Reserve, and is being replaced by Jerome Powell. Yellen was seen as fairly dovish on inflation, tending to keep rates lower for longer to spur higher employment. Powell is a bit more hawkish and is seen as more likely to raise rates more quickly to fight inflation. That goes to the whole thing we were talking about with the Fed yesterday.

Beyond that, which I think is a bit of a Red Herring, there aren’t any fundamental economic problems that are causing this. In 2008 the mortgage crises exposed the rotten foundation of the banking industry; in 2001 the internet bubble popped and exposed massive accounting frauds; in the 1970s OPEC exercised considerable cartel power (something that I wrote about here as unlikely to occur again).

That’s a quick rundown of all the major stock market disasters of the past 60 years. I don’t think there are any fundamental issues like that which we are uncovering to cause that to happen now. Rather, while we remember those three listed above, just like August 2011 there are a dozen mini-disasters that turned out to be much bigger bark than bite. I think that’s what we’ll have here.

- What I think is going to happen

Making predictions on the stock market is a sure way to look stupid, but I’ll do it anyway.

I think we’re definitely in for a wild month. I bet today (Tuesday 6-Feb-2018) the market will be up 200 points, then down 300 and another 500 the next two days. We’ll have a ton of volatility for the rest of the month, and we’ll end February down 4.8%. For the year, I will stick with my prediction from December 2017, and I think we’ll be up 5%.

What am I basing that on? A lot of gut, and that’s never a good thing. The market has had an unprecedented run. These things can’t last forever, and the market does take “breathers” (sometimes called corrections). I think that’s what we’re going through right now.

However, the fundamentals are strong. The tax break is a big boon. Even more important, the tax break and a lot of other things are spurring innovation. Money is being deployed in R&D instead of sitting in banks in Ireland and Switzerland.

Being as involved as I am in the medical device space, I know tremendous innovation is happening. Diabetes is on the brink of being cured by Medtronic; bear in mind in the US we spend about $250 billion (read that again, a quarter TRILLION) to treat that. Think of all the benefits that will follow. Also we’re on the brink of having driverless cars which that alone will create well over a trillion dollars in sales and societal benefit. Those are just two of probably a dozen you could rattle off. Bottom line, I think things are really good right now.

- How this should impact your portfolio

It shouldn’t. Definitely this shouldn’t scare you off into selling your portfolio. There’s a famous saying in the stock market that says “You should be scared when others are greedy, and you should be greedy when others are scared.”

A week ago stocks were flying high and everyone was greedy. As it turns out we should have been scared, but hindsight is 20/20. Now that everyone is scared, we should be greedy.

That said, I wouldn’t try to time the market either. A friend, Mr Snow Leopard, has a bit of cash sitting on the sideline and we were chatting about this and what to do. I said if it was me, I would invest in equal installments over the next three or so months. I know that goes against my analysis on how to invest a windfall, but I think things are so crazy right now, I wouldn’t feel comfortable putting all the chips in on one hand. I’m going with my heart over my head, but oh well.

I think we’ll definitely be in for a rocky ride and I think there are going to be a few of these really good buying opportunities interspersed with glimpses of optimism. Either way, DEFINITELY DON’T PANIC AND SELL OUT.