I’m trying to build my audience, so if you like this post, please share it on social media using the buttons right above.

Saving for college is a major issue when it comes to personal finance. When I talk to people, it’s nearly universal that people say their financial goals are to “have enough to retire comfortably” and to “pay for their kids’ college so they don’t come out with loans.”

If that is your goal, that begs the question: How much should you be saving each month?

Obviously this is a very complicated question. This is not a one-size-fits-all situation since there are so many details that make can make things vary substantially. Probably the biggest one is how much the total cost of attendance will be for your kid’s particular institution. That said, we can look at some broad averages.

The type of school

As you know, I actively question the value that colleges deliver in this day and age. When I look at the costs of attendance, that just reinforces the idea that colleges are WAY OVERPRICED. That said, let’s assume we have two broad choices for college:

In-state: Parents will get a huge break if their kids go to a public in-state school. The “top” state school in each state tends to cost about $25k for total attendance. Certainly there’s a range—UCLA is about $34,000 while University of Massachusetts is about $19,000. However, don’t think those lower costs are charity. Your tax dollars are subsidizing those lower costs.

The cost of University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, in our home state, is about $24,000. Also, that’s a number that easy to work with since it’s divisible by 12, so let’s go with that. We’ll assume that in-state expenses at a good school are about $24,000.

Private/out-of-state: If you don’t take advantage of that in-state subsidy, costs get higher very quickly. Private schools can range from about $25,000 to as high as $70,000. Since most of the schools that you think of when you think of private colleges—Harvard, Duke, Notre Dame, etc.—are in that $70,000 range, let’s use that as our number.

How much to save

Maybe time got away from you and you are getting a really late start. Your child is entering college this year. The math here is pretty easy. Each month you’ll have to come up with 1/12 of the annual cost of college. For a public school, that’s $2000 per month and for a private school that’s about $5800 per month.

Those are big numbers, but the good news is if you plan for it and are able to save sooner, those monthly contributions become a lot more manageable.

If we look at the other extreme, we can calculate what would happen if you started saving when the child was born. This is a bit more complicated because there are two powerful factors at play.

First, tuition costs for college are always rising (I’ll spare you my rant, but suffice it to say it’s ridiculous). Let’s assume that on average college costs increase about 3% each year. That means that $24,000 annual cost for a state school this year will be compounded 18 years by the time your child enters college. That’s a big deal, increasing the cost from $24,000 to about $43,000. Ouch!!!

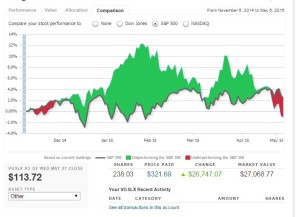

Time doesn’t help us there, but it does help us in the way you probably expected. Second, the money we save each year can be invested. If we assume a 6% return, that becomes really powerful, as we all know.

The calculations aren’t easy and I do them on a spreadsheet. At the end of the day, you’d need to save and invest $350 each month to pay for a child’s 4 year public college education. If you go private, that number increases to a bit over $1000 each month.

Of course, real life probably puts most of us in the middle between those two extremes—starting when the kid is born and starting when the kid starts college. This makes sense. When the kid is born there are a lot of expenses and other things going on, so it’s not always easy to start right away.

Here is a table that shows how much you’d need to start saving each month based on the year you start.

| Kid’s age you start saving | Public | Private |

| 0 | $351 | $1,024 |

| 5 | $460 | $1,343 |

| 10 | $650 | $1,896 |

| 15 | $1,070 | $3,119 |

| 18 | $2,000 | $5,833 |

I don’t know if that chart fills you with optimism or pessimism. Obviously the sooner you start the less you have to save. I was a bit surprised by how much just a few extra years helps. If you started saving when your kid is 15, you have to save about half of what you’d need to if you started when they enrolled. That just shows that it’s never too late to start.

On the other side, if it takes you a few years to get everything lined up, and you don’t start saving until the child is 5 years old, you don’t have to come up with a lot more than if you started when the kid was born. So that means you shouldn’t beat yourself up too much if you had to wait a bit.

Either way, if you decide that college is right for you child and that you want to help them pay for it, I hope this helps put those financial requirements into perspective.