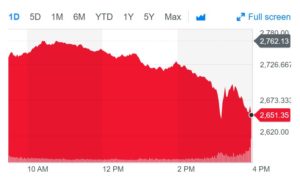

With the recent craziness in the stock market, I’ve chatted with friends about how much of their portfolio should be in stocks. Actually the conversation goes more like:

THEM: I am about 50% stocks, 50% bonds. How does that sound?

ME: 50% stocks and you’re 41 years old, and you have a good job?!?!?!? Are you crazy? That’s way too conservative.

THEM: But I don’t want to be too risky.

ME: You have a lot of safe investments that you probably don’t even know about. The investments you can invest in stocks you should so you can get the higher return over the long term.

THEM: ??????

So here is what I am talking about–the hidden cash in your portfolio.

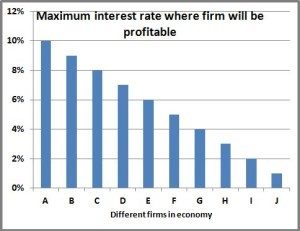

We know that you need to balance risk and return in our investments. This is most clearly done when we choose our mix of stocks (more risky, higher average returns) and bonds (less risky, lower average returns). As an investor gets older they want to shift their asset allocation towards less risky investments because their time horizon is shortening. We all agree with this. So where is this hidden pot of gold I’m talking about?

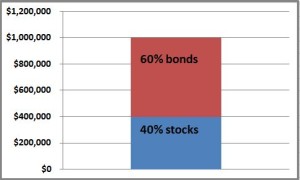

Let’s look at the example of Mr and Mrs Grizzly. They are both 65 years old and entering retirement. They worked hard over the years and socked away $1 million that will see them through their golden years. They do some internet research and learn that a sensible asset allocation in retirement is 40% stocks and 60% bonds, so they invest $400k in stocks and $600k in bonds. Knowing the long term average returns are 8% for stocks and 4% for bonds, they expect their $1 million nest egg to generate about $56,000 per year ($400k * 8% + $600k *4%) , knowing that some years it will be more and some years it will be less. So far so good, right?

THEY ARE LEAVING MAYBE $20,000 PER YEAR ON THE TABLE. That’s a ton of money. How can this be? They seem to be doing everything right. The answer is they are being way too conservative with their asset allocation. They shouldn’t be investing $600k in bonds and $400 in stocks; stocks should be a much higher percentage.

Waaaaiiiiiiiittttttttt!!! But didn’t we agree that about 60% of their portfolio should be in less risky investments? Yes, we did. Are you confused yet?

Hidden cash

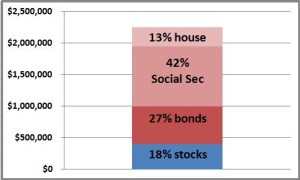

Here’s what I didn’t tell you. Mr and Mrs Grizzly have other investments that act a lot like bonds that aren’t included in that $1 million. Both Mr Grizzly and Mrs Grizzly are eligible for Social Security with their monthly payments being $2000 each. If Mr Grizzly (age 65) went to a company like Fidelity and bought an annuity that paid him $2000 each month until he died (doesn’t that sound a lot like Social Security), that would cost about $450k. So in a way, Mr Grizzly’s Social Security payments are acting like a $450k government bond (theoretically it would be worth more than $450k since the US government has a better credit rating than Fidelity). And remember that Mrs Grizzly is getting similar payments, so as a couple they have about $900k worth of “bond-ish” investments.

Also, Mr and Mrs Grizzly own their home that they could probably sell for $300k. They don’t plan on selling but if they ever needed to they could tap the equity in their home either by selling it or doing a reverse mortgage. So in a way, their house is another savings account for $300k.

If you add that up, all the sudden the picture looks really different. They have about $950k of Social Security benefits that have the safety of a government bond. Plus they have that $300k equity in their house. That’s $1.25 million right there.

Investing your portfolio

So now let’s bring this bad boy full circle. Remember their $1 million nest egg they were looking to invest? Look at that in the context of their Social Security and house. Now their total “assets” are about $2.25 million. If you believe that the Social Security and house kind of feel like a bond, just those by themselves account for 55% of their portfolio. If on top of that if you invest 60% of their $1 million nest egg in bonds, they have over 80% of their money in bonds, and that seems way too high.

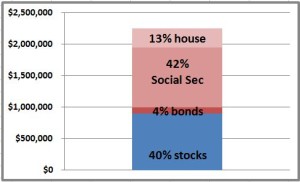

On the other hand, let’s say they only put $100k of their nest egg into bonds and the rest into stocks, after you include their social security and home, they’d be at about 60% bonds and 40% stocks. Isn’t that what they were aiming for the whole time?

Wow. It took a long time to get there, Stocky. The punchline better be worth it. Remember that with $600k in bonds and $400k in stocks, they had an expected return of about $56,000 per year. However, if they have $100k in bonds and $900k in stocks, because stocks are more volatile but have a higher expected return, they can expect about $76,000 ($900k * 8% + $100k *4%). THAT’S $20,000!!!

But aren’t they taking on a lot more risk to get that extra $20k? Remember, there’s no such thing as a free lunch. For sure, but if you look at it in the context of their Social Security benefits and their home, they have a fair amount of cushion from “safe investments” to see them through any rough patches in the stock market.

I wrote this post to show that people really need to take account all the financial resources they have. In the Grizzly’s case, it was their Social Security benefits and their home. Others of you may be getting a pension (Medtronic is generous enough to offer the Fox family one) or a second home or a dozen other things like that.

When you take those cash flows into account, all the sudden it seems a lot more reasonable to invest the rest of your money a little more heavily in stocks which you know over the long haul will give you a better return.